The following descriptions of territories of life across West and Central Asia were collected from the ICCA Consortium membership in the region. Cases have been grouped based on the ecosystems where these ICCAs exist.

Traditional fishermen of the coastal lagoons in Turkey. Photos: Engin Yılmaz

15

Traditional fishermen of the coastal lagoons in Turkey

Preserving biodiversity through traditional fishing practices

Source: Engin Yılmaz, Yolda Initiative

Location: Coastal lagoons on the Mediterranean Shore in Turkey

Community: Traditional fishermen

Practice(s): Traditional trap fishing and artisanal fisheries

Traditional trap fishing (dalyancılık) in the coastal lagoons along the Mediterranean shores in Turkey is one of the most ancient fish trapping techniques in the world, practised for centuries. Before World War I, the practice was mostly conducted by the Greek population in the Aegean region, as still acknowledged by fishermen today. Wetlands are among the most threatened ecosystems globally. Turkey is likely to be one of the countries which has lost the most wetlands in the 20th century, largely due to water abstraction upstream for creating agricultural lands and energy production.

Coastal lagoons are among the priority wetlands in Turkey, with threats including:

- Decreasing or full stop of freshwater input due to water abstraction

- Abandonment of traditional practices and lands

- Land loss/fragmentation/degradation

- Shallowing

- Pollution

- Illegal fishing and overfishing

- Climate change

Lagoons are modified natural ecosystems which over hundreds of years of trap fishing became a unique example of coexistence between humans and natural processes. Thus, human activities do not only threaten the lagoons (as outlined above) but they also may be beneficial and result in the conservation of these wetlands and also the marine biodiversity including high trophic level fish species – such as through traditional cultural practices of local communities.

As these local lagoons are critical ecosystems for fish populations as nursery areas and feeding grounds, their richness made traditional trap fishing one of the main income-generating activities for local communities for thousands of years. This practice consists mainly of setting up traps made of sticks and nets by the coastlines of the lagoons. The objective is to trap fish of a certain size so the young fish and fish eggs are not destroyed. The method also allows a certain amount of fish to escape the nets, thus preventing overharvesting of fish populations. Although there are minor changes regarding the opening and closing season for each lagoon, this method is in harmony with the natural cycle as the traps are set up at the same time every year, coinciding with the times when fish migrate from lagoons to the sea, catching only a sustainable amount. This practice has important positive impacts on the lagoon ecosystems by maintaining high levels of both marine and terrestrial biodiversity.

Considering the diverse flora and fauna they host, all the lagoons where these practices take place are under protection by national legislation, and some also by international conventions.

The fishermen communities at the lagoons are organised in cooperatives in which the number of members varies depending mostly on the production levels. These cooperatives manage the lagoons based on contracts signed with the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry. Thus they are not a part of the governance mechanism per se but can only hold the limited responsibility of managing the lagoons for a certain time as stated in contracts. Additionally, their rich traditional ecological knowledge which is crucial for the sustainability of these ecosystems is not recognised and respected by the decision-making authorities and also in most cases by the academics who are closely involved with these authorities.

In sum, the fishermen in these lagoons represent a wealth of traditional ecological knowledge in terms of natural resource management, which to date has remained largely unrecognised within the conservation community even though it holds a key for a more sustainable future. We can greatly benefit from such tried and tested community perspectives and practices, which have stood the test of time and could be extremely beneficial on a broader scale in the future.

Herders in the Ysyk-Kol region. Photo: Aibek Samakov

16

Sacred sites in the Ysyk-Köl Biosphere Reserve in Kyrgyzstan

Sacred sites in the Ysyk-Köl Biosphere Reserve: promoting biocultural approach to conservation

Source: Aibek Samakov, ICCA Honorary Member

Location: Ysyk-Köl (Issyk-kul) Province, Kyrgyzstan

Community: Various local communities

Practice(s): Traditional spiritual/religious practices

There are more than 1,000 sacred sites across Kyrgyzstan. Sacred sites have been a part of many Indigenous cultures around the world (Verschuuren et al. 2010). Although the ‘sacredness’ of a place may stem from cultural, religious, and spiritual domains (Aitpaeva 2009) and may not explicitly refer to conservation, oftentimes sacred sites have a positive effect on biodiversity conservation. Sacred natural sites are usually defined as “areas of land or water having special spiritual significance to peoples and communities” (Verschuuren et al. 2010, p.1) and have been protected by local communities around the world for centuries. In some communities (for instance, across Asia and Africa) sacred sites have been better protected than most officially protected areas (Dudley et al. 2005). Moreover, some formally protected areas were established around existing areas that had been already protected by local communities through traditional “conservation practices, including some elaborate and effective systems” (Borrini et al. 2004, p. 20). Sacred sites are present in all countries of the West and Central Asian region. In most countries, sacred sites are not officially recognized and function as informal institutions, whereas some countries have started to take steps toward recognising them. For example, Kazakhstan launched a state-backed program called Sacred Geography of Kazakhstan, which aims to document and conserve sacred sites in the country.

Some of the sacred sites are located within formally protected areas. Sacred sites are revered by local communities as places of purity, divine energy, and force. People visit sacred sites individually or in groups and conduct various rituals such as healing rituals, rights of passage, etc. The reasons for visiting sacred sites are very diverse and vary from specific reasons such as asking for good health, progeny, wealth, luck, etc. to more generic spiritual reasons such as selfimprovement and purification.

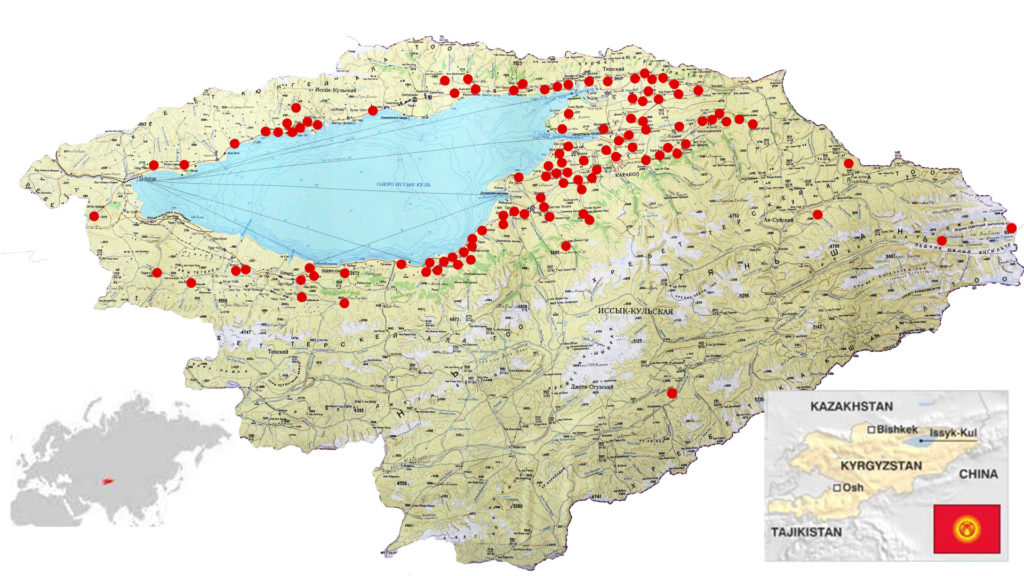

There are more than 130 documented sacred sites in Ysyk-Köl Province of Kyrgyzstan (Figure 5). They are very diverse in terms of size and biophysical elements encompassed by a particular sacred site. It is believed that sacred sites are the ‘umbilical cord’ that connects communities to their territories of life. For example, a sacred site can consist of several springs and trees or entire ecosystems such as Lake Ysyk-Köl or Khan-Tengiri Mountain.

The unique feature of sacred sites in the Ysyk-Köl region is that they are located within formally protected areas. Up until recently, the Directorate of the Biosphere Reserve did not take into account sacred sites in its conservation strategy. Nowadays, the Biosphere Reserve recognises the positive role of sacred sites in biodiversity conservation and believes that the incorporation of sacred sites can improve biocultural conservation in Ysyk-Köl Biosphere Reserve (YKBR) in the following nine ways: 1) making the concept of Biosphere Reserves more understandable for local communities, 2) improving ecological monitoring, 3) indirectly conserving species and areas, 4) improving biosphere reserve zoning, 5) providing a complementary culture-rooted set of incentives for conservation (in addition to external incentives), 6) fostering a biocultural approach to conservation, 7) collecting and using traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) in conservation, 8) serving as a communication hub for YKBR managers and local communities, and 9) serving as a platform for local communities’ capacity building.

Sacred sites in Ysyk-Köl province as well as throughout Kyrgyzstan are conserved and protected by local communities for spiritual and religious reasons. Due to the rules and taboos related to the sacred sites, they have become local biodiversity hotspots. However, the anti-religious policies during the Soviet times disrupted the connections between many local communities and their sacred sites. The visits to sacred sites were prohibited and the sacred sites practitioners were prosecuted by the authorities. Since regaining independence, many communities have reestablished the tradition of visiting and protecting sacred sites. However, there are still challenges preventing the sacred sites in the Ysyk-Köl province from becoming defined ICCAs. First of all, there is no recognition of sacred sites in the national legislation. Secondly, some new movements within Islam condemn as idolatry the tradition of visiting sacred sites, which is at odds with the traditional perceptions of sacred sites.