- Home

- Executive summary

- Territories

- Kisimbosa – DR Congo

- Yogbouo – Guinea

- Fokonolona of Tsiafajavona – Madagascar

- Kawawana – Senegal

- Lake Natron – Tanzania

- Qikiqtaaluk – Canada

- Sarayaku – Ecuador

- Komon Juyub – Guatemala

- Iña Wampisti Nunke – Peru

- Hkolo Tamutaku K’rer – Burma/Myanmar

- Fengshui forests of Qunan – China

- Adawal ki Devbani – India

- Tana’ ulen – Indonesia

- Chahdegal – Iran

- Tsum Valley – Nepal

- Pangasananan – Philippines

- Homórdkarácsonyfalva Közbirtokosság – Romania

- National and regional analyses

- Global analysis

The Manon peoples of the forest and mountainous region of the Republic of Guinea proudly practice their customs, preserving their local ancestral memory and traditions that have been passed down from generation to generation. Manon society considers this their cultural and environmental heritage, linking the past, present and future.

The Yogbouo Pond of Gampa is a living example of this culture. This sacred site and its surroundings are home to a remarkable flora and fauna consisting of woody vegetation, with large trees, and various endangered species including the hippopotamus and chimpanzee. In addition, several mysteries, tales and legends, told over thousands of years, have contributed to this environment’s rich cultural heritage.

“Initiation in the sacred forest is the most exciting part of our existence, and the most vibrant element of our community. In the initiation forests, we find and strengthen our values. And the Yogbouo Pond is where we find solutions through prayers and offerings.“

Pé Gbilimy, community member of Gampa

Photo: Jean Baptiste Koulemou

176 hectares

Custodians: Community of Gampa 1,800 inhabitants

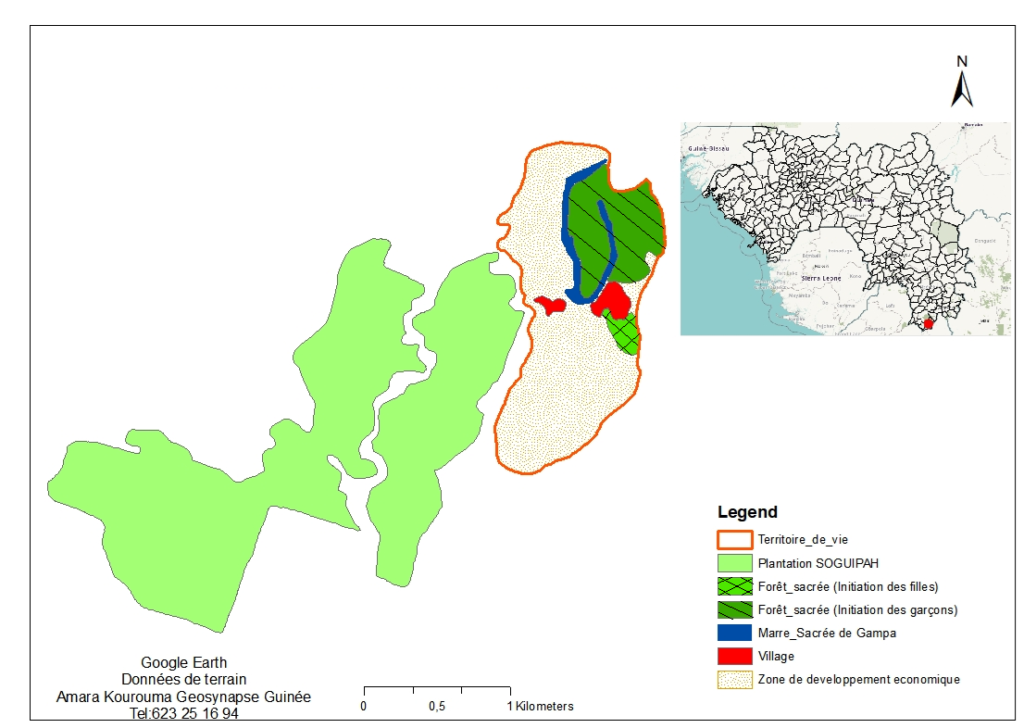

The Gampa territory of life has a surface area of 176 hectares (located 07°15 N / 08°50 W). The Yogbouo sacred pond is located in the extreme south-east of Guinea, on the edge of the village of Gampa, and 22 km from Diécké, headquarters for the Guinean Society of Oil Palms and Heveas (SOGUIPAH), as well as the sub-prefecture. It is bordered to the south-east by the Mani River, which marks the border between the Republic of Guinea and the Republic of Liberia, to the west by the industrial plantation of SOGUIPAH (which borders the territory of life), and further north by the Diécké protected forest, located 10 km from the territory of life.

This territory of life is composed of a sacred pond of 9.8 ha, a men’s initiation forest (37 ha) and a women’s initiation forest (4.6 ha), an area dedicated to subsistence farming (food crops, fallow land, livestock, fish cultivation, gathering, and hunting) of 118 ha, and a habitation area (6 ha).

The sacred pond Yogbouo is an “invisible entity”, a place where individual and collective misfortunes are resolved. It ensures the protection of approximately 1,800 inhabitants of the villages of Gampa against harmful forces and is involved in many therapeutic rituals where the officials in charge of the site also welcome visitors from other neighbouring or distant communities.

Endowed with rich biodiversity, this ecosystem offers a peaceful and safe habitat for wildlife. This highly humid environment near the Diécké protected forest (64,000 ha, classified as a State Protected Area) represents a space of significant ecological value, favourable to the development of diverse forms of life. The region is an important area for birds, home to large endangered mammals such as pygmy hippopotamus, several species of fish, crab and reptile – in particular, pythons and crocodiles – and also forms a refuge for various large mammals coming from neighbouring Liberia.

The guardians of the sacred pond

The story of the Yogbouo Pond, with its biodiversity, ecological benefits and cultural values, willingly conserved by the local community, is truly compelling. According to patriarch Nyan Mizi Simmy, the pond became sacred following the decision of women from Gampa to fish in the pond without any authorization. When the women entered the water, they all disappeared and were never found again. The villagers then began to cry and lament their cruel loss, hence the pond’s local name, “Yogbouo”, which means “too much crying” in Manon. Now, offerings are made to the genies during various ceremonies.

In this region, sacred sites, which include the pond and the surrounding forest, are the exclusive property of a clan or a tribe (Maomy, Sandy, Mamy, etc.) and are where these groups make sacrifices in homage to their ancestors, asking for their help to satisfy a specific need or overcome a particular problem. These forests also symbolize the origins of totemism where an event experienced by an ancestor achieved success or defeat in war.

Totemism

Among the Manon, families are patriarchal and organized in patrilineal clans. A clan designates all the descendants of a mythical ancestor associated with one or more species, animal or plant, which is then forbidden to be eaten or killed by that clan. For example, the Maomy do not eat the meat of the panther and the Sandy do not eat the flesh of the boa constrictor. The Manon refer to these proscriptions as “totem”. Other prohibitions also exist in different clans, such as sitting on a mat made of a certain grass or, for the Loua clan, wearing boubous and striped loincloths. For most forest peoples, breaking the ban results in swelling or scabies or other skin diseases, which are signs of contamination.

In general, there is no single divine or supra-terrestrial understanding of the origin of these different proscriptions, with each prohibition having its own origin story. However, amongst the forest dwelling communities of Guinea, there are various ideas and traditions, unique to each community, which help explain the origins of totemism. The four main reasons for adopting these proscriptions are: familiarity or resemblance with the person; indications given by the diviner; services provided; and fear. Amongst the Manon, the sacred forest also constitutes a temple of fetishism and a sanctuary where secret rites and ceremonies take place.

For the Manon of Gampa, the relationship with this aquatic environment, and the forest island that surrounds it, is one of dependence for survival. Each individual (man or woman) of this clan has their corresponding pairing in the forest or pond, among its wild and aquatic animals and fish. And it is they alone who know the secret of metamorphosing into their own species (man-antelope, man-panther, man-boa, woman-wing, etc.). This is the reason why the Manon Indigenous populations are resolutely attached to the ecosystem in their territory, regarding it as a fundamental source of life.

The council of elders

In Gampa, traditional authority plays an important role in the management of the territory and structures the governance of the village community. This community is headed by a customary chief, and follows two basic structures of governance, one vertical and one horizontal: (1) the household family, extended family, lineage and clan constitute the vertical structure; and (2) the brotherhood of officials responsible for sacred worship constitutes the horizontal structure. There is an intimate relationship between these two structures, which complement each other in the processes of managing community affairs and the use of resources from the pond and elsewhere in the territory of life.

A council of elders ensures the governance of local resources; it is responsible for making decisions about the management of all the village’s natural resources. This council also makes decisions on all social issues, including conflict and dispute management. The council acts as the community’s voice and expresses their concerns or needs to the state. The state, for its part, respects the existence of the pond as part of the community’s cultural and environmental heritage. Article 19 of the Constitution of Guinea states: “The people of Guinea have an inalienable right to their wealth. [And] to the preservation of their heritage, culture and environment.”

Customary management rules are dictated and applied by the council of elders, who then propose them to the village council. These rules include, for instance, the allocated periods of fishing, harvesting of wild fruits, or setting the dates of ritual ceremonies and initiations. Here the local rules are established to better protect the environment, prohibiting the exploitation and consumption of certain species of plants and animals at certain times of the year. Outside of rituals and/or annual collective fisheries, the access to the sacred sites is strictly limited: only a select category of persons, who carry a specific tattoo, are allowed to go there.

Customary systems of resource management are dominant in rural areas where land and resources are inalienable, and access to land is secured by social identity and belonging to the lineage group. In Gampa, customary law is under the control of families and lineages that have the historical and social status of “first occupants”: they have rights of access to and control over resource use and management.

Nyan Mizi Simmy (member of the council of elders) on the rules and sanctions around the sacred pond.

Conservation and biodiversity

The primary forest surrounding the sacred pond is home to large tree species such as the irokos (Milicia excelsa), the African locust bean (Parkia biglobosa), and the bombax costatum. The territory’s fauna include several species of fish and mammals such as buffalo, harnessed bushbuck, several species of duikers, primates such as chimpanzees, the black and white colobus, the bay colobus, and the diana monkey, as well as the pygmy hippopotamus and panther. The entomological fauna is also very rich.

In Manon country, the plant and animal world constitute cultural and environmental heritage carefully nurtured over several millennia, which provides important treatments for several human and animal diseases, as well as offering key nutritional benefits. One key resource is natural palm oil (Elaeis guineensis), the main source of edible oil in the forest region. Its branches are also used to cover huts and huts. Another key resource is raffia (Raphia sudanica), which produces wine of the same name and is a major element of identity and pride. It is used as an alcoholic beverage and generally consumed in groups to stimulate the completion of agricultural work, wedding ceremonies, baptisms and other occasions and festivities. Its sap, raw or processed, is also used in the treatment of measles.

The people of Gampa also derive several economic and environmental benefits such as production of fish and timber for construction and energy, and protection of houses against strong winds and climatic hazards. The surrounding forest is thus considered by the community as a “green lung” that allows them to live.

Threats and responses

Pressures from development, religion and climate all have impacts on the territory, its resources and culture. In the face of growing land pressure from oil palm and rubber plantations – established by the “SOGUIPAH” industrial company, which has been present in the region since 1987 – several animal and plant species of the sacred pond and its associated ecosystems are currently under threat, which is leading to progressive loss of resources. For example, Iroko timber is being excessively exploited in the surrounding area.

Monotheistic religions (Islam and Christianity) also have a strong disruptive influence, capable of causing major transformations in human-nature relations, and in the value and belief systems they induce. The increasing influence of these religions, together with formal education, has seen a significant reduction in sacred forest areas and a gradual abandonment of the community’s traditional practices and customs. For example, rituals in sacred forests that generally used to last seven years have now been reduced to only three months.

Another threat is the year-on-year decrease in the amount of water contained in the pond, probably due to nearby deforestation and the effects of climate change. This is a major concern for the community, which is relatively powerless to cope with it.

However, the main conflict around the Gampa Pond continues to be related to the SOGUIPAH company. According to the inhabitants of Gampa, in the 1990s, this company had asked the state for a portion of the forest island in the middle of the pond to extend its palm plantations. This request was rejected by the community of Gampa, thus avoiding the expropriation of part of the territory. The rejection of this company’s request comes from the local customary structure which, until now, has remained resolutely opposed to the influence of the central state structure.

François Saoromy talks about the conflict with the company SOGUIPAH.

Today, the nature of the relationship between SOGUIPAH and the neighbouring communities remains deeply conflicting because of the opacity in its management and the failure to implement various collaboration agreements; one that was drawn up on 19 June 1986 protects places of worship and land reserved for field work and village plantations.

In a memorandum addressed to the President of the Republic published in the local newspaper “Ziama Info” on 30 January 2014 under the title “SOGUIPAH: The anger of the local communities”, Michael Sonomy, spokesperson for the youth, writes: “The various collaboration agreements signed between SOGUIPAH and the population of the two communities are concealed by the company’s managers to such an extent that no one in Diécké and Bignamou [the two neighbouring rural communes whose territories are occupied by SOGUIPAH] can clearly define the company’s social and environmental responsibility towards these communities… The populations of the two localities are confronted with enormous difficulties, including the inadequacy of environmental protection measures…”

Despite these various threats, however, there are opportunities for the sustainable and community-driven development of territories of life in Guinea. Local communities show willingness to preserve their natural and cultural heritage and there is high value of the goods and services generated by their collectively conserved territories and areas. In addition, the local government legislation considers the views of customary authorities and international cooperation supports community-based initiatives.

“The community and the SOGUIPAH company have diametrically opposed objectives: we seek to protect our resources through our customary rules, they are the opposite, what interests them is the extension of palm tree plantations; ultimately, this would mean for us to lose our farmland, our sacred sites and our cultural identity.”

Gampa: A vision for the future

According to a retired former civil servant, Ouo Sangbalamou, in order to bring about the required changes and raise the issue of the Gampa Pond to the top of the national agenda, “it will be necessary to foster synergies with other national projects and programs working in the same direction or for similar causes, and mobilizing other institutions accordingly. Furthermore, it will also be necessary to increase awareness among the youth of the importance of endogenous ancestral knowledge and practices, for example on the subject of sacred forests and the transmission of traditional knowledge, two of the most important subjects in the Manon environment.”

Mr. Nyasson, a youth representative, states that it will be important to “set up a sustainable financing system for the sacred pond and associated ecosystems in order to preserve its long-term biodiversity and threatened species therein”. For Mr. Togba Zomou, a member of the council of elders, it will also be necessary to “strengthen the legal and physical protection of this key forest area [the initiation forest for boys and girls], not only because it is home to totemic plants and animals and other species, but also because it is an important area for the ecosystem services provided by the transition zone between the Yogbouo Pond and the Diécké protected forest.”

To do this, local communities today need the support of international agencies, national governments, and civil society more generally, to help them tackle their challenges, old and new, particularly in the context of future environmental, health or social crises. These crises have a serious impact on the income of farmers who are sometimes forced to draw on their seed reserves for food or to turn to other illicit activities such as poaching and illegal fishing in the conserved areas. To avoid this and to help the population of Diécké and Bignamou as much as possible, various solutions are proposed such as:

- Promoting market gardening on small irrigated areas managed by women’s collectives;

- Promoting village fish farming to improve the resilience of local communities in Gampa;

- Strengthening traditional Indigenous conservation methods for the sacred Pond of Gampa by emphasising the importance of their traditional rules; and

- Supporting the conservation and development of the natural and cultural heritage of the initiation forests for the men and women of Gampa’s territory of life.

References

Debonnet Guy, Collin Gérard. 2007. Rapport de mission de suivi réactif UNESCO/UICN à la Réserve Naturelle Intégrale des Monts Nimba, République de Guinée. World Heritage Centre/IUCN.

Germain, Jacques. 1984. Guinée : Peuples de la forêt. Historique du peuplement Manon. Paris: Académie des Sciences d’Outre-Mer.

Ziama Info Journal, 30 Jan. 2014. La colère des communautés locales.