- Home

- Executive summary

- Territories

- Kisimbosa – DR Congo

- Yogbouo – Guinea

- Fokonolona of Tsiafajavona – Madagascar

- Kawawana – Senegal

- Lake Natron – Tanzania

- Qikiqtaaluk – Canada

- Sarayaku – Ecuador

- Komon Juyub – Guatemala

- Iña Wampisti Nunke – Peru

- Hkolo Tamutaku K’rer – Burma/Myanmar

- Fengshui forests of Qunan – China

- Adawal ki Devbani – India

- Tana’ ulen – Indonesia

- Chahdegal – Iran

- Tsum Valley – Nepal

- Pangasananan – Philippines

- Homórdkarácsonyfalva Közbirtokosság – Romania

- National and regional analyses

- Global analysis

Homoródkarácsonyfalva village (hear pronunciation; English: Christmas village; Romanian: Crăciunel) is nestled in the valley of the Homorod stream, in the scenic foothills of the eastern rim of the Carpathian Mountains, South-Eastern Transylvania, Romania. The community identifies as Szekler (székelyek), a subgroup of the Hungarian-speaking people and an ethnic minority in Romania. It is an area with a rich silvo-pastoral culture, entangled with a recent history of centralized socialist economic modernization. In 2000, the community has regained communal rights over pastureland and forests that were confiscated and passed to state ownership by the socialist regime (1948-1989). Since then, the community has also seen a turn towards nature conservation, including a return of emblematic species, and lower rates of forest harvesting. As a special feature, in the whole region, ancestral systems of common rights and traditional ways of rights distribution have survived, although transformed, despite impositions by successive legal reforms.

“During communism we did not have full control of our lands and this affected our capacity to self-organize, to strategize and to nurture the community. Since we received our commons back, we started to think as a collective again, to plan for the future.“

Csaba Orbán, President of the Közbirtokosság, 2021

Photo: Csaba Orbán

1,098 hectares of land in total

732 hectares of forest

347 registered rightsholders

We are who we were, and we will be who we are

The community defines itself strongly in relation to ancestry and past landholding traditions, which enabled them to remain free landholders and to prosper during periods of hardship for most Eastern European communities (Imreh, 1973, 1982).

The present communal landholding system goes back to the older rights systems, with a communal freeholding regime recognised by the medieval and early modern Hungarian Kingdom as a privilege given in exchange for border defence services (Varga, 1999). Towards the end of the 19th century, the Közbirtokosság was constituted as a formal institution in charge with governing the commons according to by-laws (Dezsö, 2002).

“Vagyunk, akik voltunk, és leszünk, akik vagyunk – We are who we were, and we will be who we are.”

After the First World War when Transylvania was annexed by the Romanian Kingdom, the local customary institution (Közbirtokosság) became recognised by the Romanian state. Up until the middle of the 20th century, the community property and land use systems followed the typical patterns of feudal silvo-pastoral villages in Europe, with a certain degree of independence in self-managing resources communally.

During state socialism (1948-1989), the communist regime nationalized the lands and put an end to this customary property regime. Forests were nationalized and managed in a state-centralized manner. Most of the agricultural land was collectivized as a cooperative. The cooperative erased the older communal rules and allowed locals to retain ownership of only one head of cattle per household, but obliged people to enrol as paid workers for the cooperative herd and deliver produce for the centralized economy (Verdery, 2003). In the socialist system, economic productivity was paramount, and an ethos of modernization and industrialization dominated land use and management (Verdery, 2001).

After the 2000s, a set of legal land reforms allowed the community to regain property and use rights to their territories.

Restoring rights to common land, a restitution moment

In the post-socialist period, in the year 2000, the communal property system, Közbirtokosság (which existed prior to 1948), was reinstated through restitution law 1/2000 and the community again took hold of pastures and forests.[1] Under this law’s provisions, Homoródkarácsonfalva Közbirtokosság was registered on 1 April 2000, with the founding document signed by the regional and local authorities along with appointed representatives of the community. The biggest challenge in the registration process was the lack of historical documents to prove rights to commons. Eventually, the commission in charge of restitution found a table mentioning the distribution of commons’ forest rights dated 1946 and a land registry from the 1890s. These documents are now framed and displayed in the main hall of the commons institution’s headquarters as a remembrance of the past (see photo ‘Historical tables of rights to commons’).

Közbirtokosság: a system to collectively govern the commons

The forest, pasture and water sources are governed by the community institution as a commons: an elected executive committee functions according to written by-laws and decisions taken by the general assembly of rightsholders. The commons are considered private property of the community, and delimited within the Romanian legal categories of land ownership as ‘historical associative forms of property’ – separate from municipality property, state property and individual private property.[2]

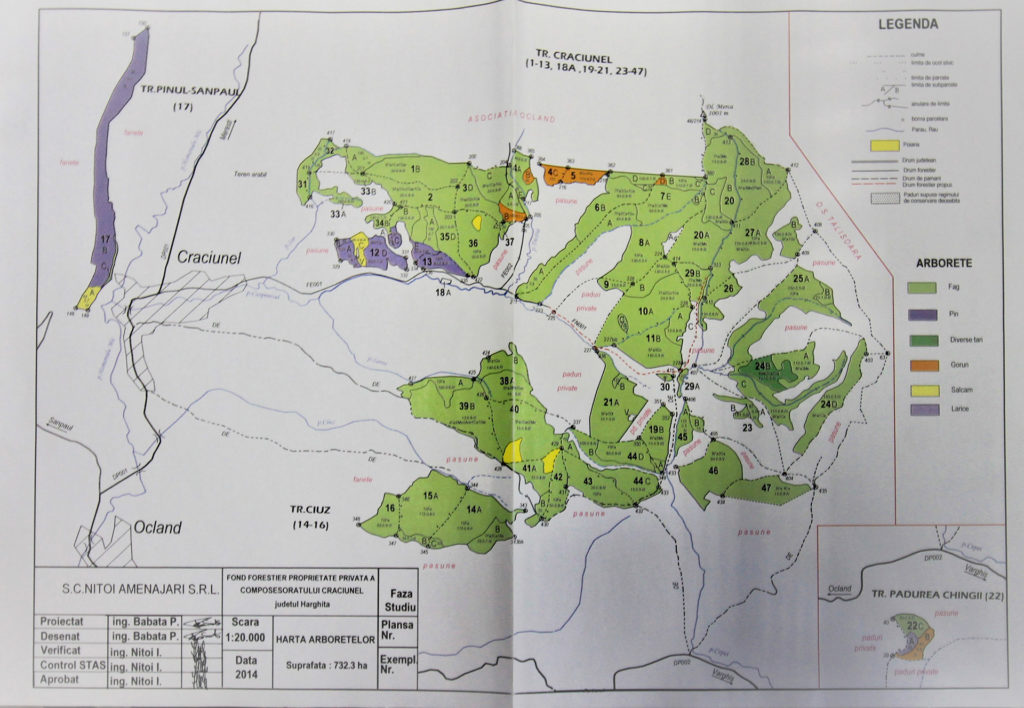

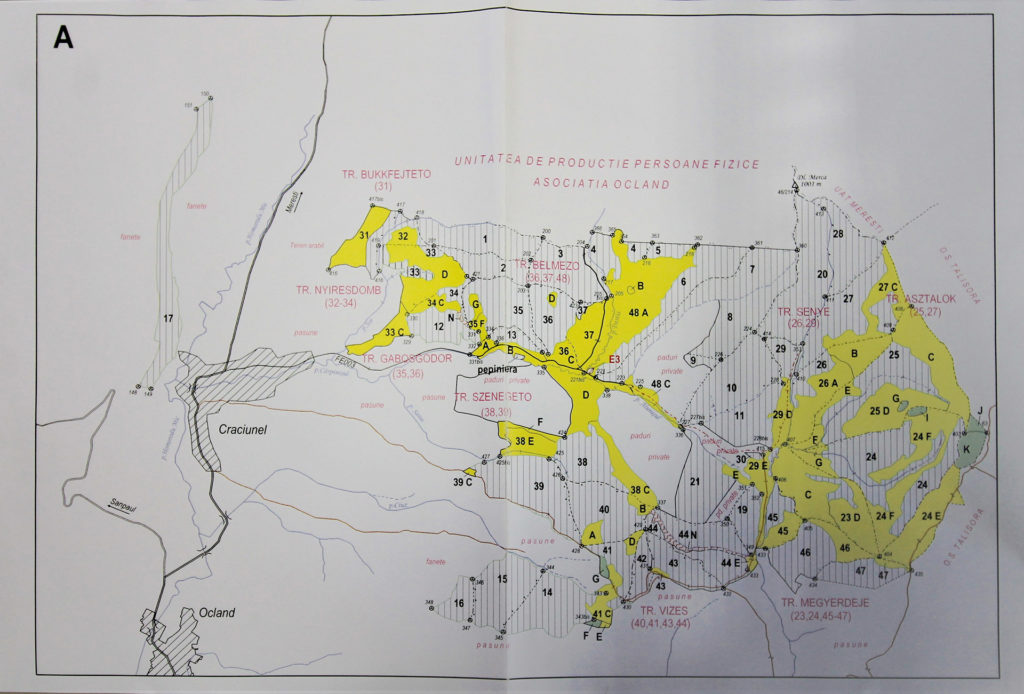

The commons has 1098 hectares of land in total, of which 732 ha are forest (with an estimated monetary value of 1,389,800 euros) and 366 ha are pastures.

There are currently 347 registered rightsholders, around half of whom reside in the village. The other half are descendants of the old rightsholders who currently reside elsewhere, though they have relatives in the village who are delegated to use the common lands and participate in decision-making processes. The Unitarian and Catholic Churches are also considered rightsholders, as entities with distinct rights given their need for firewood to heat the church and so on.

Within the community, each rightsholder has inherited rights from their ancestors. The rights are legally registered and counted as communal shares called ‘quota-parts’. Sales of shares between the members of the community of descendants are allowed but not excessively, as the rules of the commons mention that no person can inherit or acquire more than 5% of all shares. A small percentage of village families do not hold rights to the commons, such as newcomer families who moved there in the 20th century.

The rights are held by the elders and only after the death of an elder the offspring can inherit the rights. As such, some younger families do not officially hold rights or participate in communal assemblies, but have ‘arrangements’ with their parents or grandparents for using the commons. Though women and men are entitled to inherit rights to the commons, women tend to marry outside the village, and it is usually men who inherit the household and thus the common land rights. The community devised a set of clear rules to avoid challenges such as excessive division of rights and lack of participation. For example, the parents usually choose only one of their offspring as inheritor and bearer of the rights, usually the youngest one or the one that will continue to live in their house after their death. The siblings have to agree with this decision, and the governing bodies do not require certified documents to attest the inheritance of rights.

Rights to forest use are quantified and considered different than rights to pasture use (Vasile, 2019b). For each right (share) to the forest, a rightsholder is entitled to approximately 0.62 cubic meters of timber. If the member does not need the timber (for example, if they reside in the city, or can supply it from a private forest), they will receive the equivalent in cash. For each right to pasture, the member can send one cow or up to 7 sheep to graze. Those who do not need to use the pastures receive around 10 euro (50 RON) per year per right. Similarly, rightsholders who own more cattle but do not have sufficient pasture rights are allowed to acquire the grazing rights from other rightsholders who do not use them and offer compensation in return.

The communal rights are currently recognized by Romanian law (Law no. 1 of 2000) and registered in official land books and property documents. The by-laws are validated and registered with the court of law. However, the management of local resources is also dictated by overarching regulations and policies. Pasture management is subject to European regulations dictated by a policy of direct payments under the Common Agricultural Policy. Forests are additionally subjected to country-wide legislation and vested in specialized institutions – i.e., forestry districts accredited by the state, forest management plans designed by hired experts and approved by the Ministry of Environment. In addition, a series of customary documents locally regulates the use of resources, for example, the use of pasture and mineral water springs.

Revenues from commons are used in part to sponsor community activities such as the construction of a communal spa bath, the annual Chestnut Festival, the renovation of historical buildings and various other cultural activities. More recently, the governing institution started to sponsor these activities using EU direct payments. Over the years, the community built a complex of public baths around the mineral springs located in the south-eastern part of the village, called “Dungó Feredő”. Due to a set of miraculous healings, some members tend to attach spiritual values to Dungó Feredő and consider the place sacred. Other revenues derived by the community institution Közbirtokosság are used to cover the costs of its operations, such as bills and taxes, and the rest is redistributed to members of the community.[3]

The territory of life – pastures and woods

The territory of life surrounds the village and it is zoned in three main areas of approximately equal size: forestland, wood pastures and pasture. Private properties, both forests and pastures, are interspersed throughout or border the territory of life. A sweet chestnut orchard of approximately one hectare is located close to the center of the village. The pastures are divided into two categories according to seasonal use: the upper pastures are more difficult to reach and used for young cattle from April to September and the pastures around the village are used daily to graze milking cows, goats and sheep.

Wood pastures are among the oldest land use types in Europe and have high ecological and cultural importance (Hartel et al, 2013). Here, grassy vegetation forms a mosaic landscape with interspersed ancient trees, including oak, sessile oak, and beech, which represent local biodiversity hotspots. Mosaic areas offer a broad range of habitats for biodiversity and good conditions for silvo-pastoral livelihoods, grazing livestock, in shade and sun (Varga and Molnár, 2014).

Wood pastures are rapidly declining all over Europe because of changes in land use and lack of regeneration, and they are generally not recognized in the nature conservation policies of the EU or protected as distinct landscapes despite evidence from research showing their special management history and values. In Karácsonyfalva, the wood pastures were maintained by the community throughout history despite adverse state-driven tendencies. ‘Acorn’ forests were incredibly valuable in medieval Transylvania and most of Europe given the importance of acorns for feeding pigs.

During socialism, animal husbandry practices were intensified, large trees on pastureland were cut down and artificial fertilizers introduced.

“We protected the large trees on the pastureland, but many of them were cut down in the 1960s during socialism.”

After the fall of socialism in 1989, pastureland was abandoned, and scrub was not cleared thoroughly anymore. Yet, Romania’s accession to the European Union in 2007 brought direct payments through the Common Agricultural Policy, which spurred scrub clearance and pasture maintenance activities to correct the neglect of the previous years (Varga, 2006). The pasture is currently understocked with no problems of overgrazing. Most people have few animals and a few farmers have a higher number of cattle and sheep.

The forest is temperate and over 90 per cent of it is comprised of European beech (Fagus sylvatica) that is healthy and around 120-200 years old; the rest of the forest is sessile oak (Quercus petraea), oak (Quercus robur) and pine (Pinus sylvestris). Though pine was planted by the Hungarian state and considered an imposition from outside, it offers great protection to the chestnut orchard by stabilizing the land against erosion and landslides.

“Our Szekler tradition with forestry is to use methods that keep the quality of aged trees and only to cut if we need money very badly. Then we cut some, but only with the approval of the forestry district and within certain limits. We do not cut everything at once, but always think of the next generations, so that they can be at least as well-off as we were.”

The forests owned and managed as commons have two types of uses: firewood and commercial use. The community can harvest up to 2200 cubic meters of timber annually (as calculated by experts in the management plan for keeping to a sustainable yield principle), but the actual volume has always been lower, contributing to a net increase of the tree cover. The majority of timber felled is used locally as building material or for firewood. Although practiced in neighbouring communities and throughout the area, commercial felling in Karácsonyfalva dropped constantly and is now almost insignificant. The fact that the community harvests less than what they would be allowed to do and only to cover home necessities is a remarkable conservation feature for this area.

There are several forest conservation elements, including 120 hectares under voluntary non-intervention protection, where no cuts are allowed, and 30 hectares of sessile oak is under strict protection as a seeding area. It is also considered a quiet zone, which commoners believe has contributed to the return of wildlife.

Emblematic species and conservation actions

There are several vulnerable, endangered and critically endangered species of flora and fauna with important ecological functions. Oak is a diminishing species around the world; thus, this sessile oak reserve holds special importance. The black stork (Ciconia nigra), a threatened species in the EU, nests on undisturbed mature trees in the area and has been spotted by locals recently. The European beaver (Castor fiber), a species considered under threat in Europe, lives here and is welcomed by locals. Numbers of the grey wolf(Canis lupus) and brown bear (Ursus arctos) have increased in the area and country in the last five years after the Romanian government introduced a strict ban on hunting. More recently, endangered species such as the lynx (Lynx lynx) and the wild cat (Felis silvestris) have been sighted. The number of white storks (Ciconia ciconia) is increasing year after year, not only signalling a healthy habitat, but also locals’ positive attitude, as this species usually nests around houses and is considered a good omen for the health and prosperity of each family.

“We did not try to find explanations for the recent return of wildlife, we are just very happy about it.”

A Natura 2000 protected area (PA ROSPA0027) for bird protection overlaps most of the Homoródkarácsonyfalva village and commons and the surrounding villages. Among the most representative species conserved within this protected area are: lesser spotted eagle (Aquila pomarina), greater spotted eagle (Aquila clanga), common kingfisher (Alcedo atthis), black-crowned night heron (Nycticorax nycticorax), grey-headed woodpecker (Picus canus) and lesser grey shrike (Lanius minor). Locals were not consulted when the protected area was declared, as is the situation with almost all Natura 2000 areas in Romania (Iordachescu, 2019). Nevertheless, the community welcomes the existence of the protected area and has plans to seize the opportunity and build ecotourism in the village.

Since its reestablishment as a juridical entity, the governing board of the commons managed to register two protected areas of local interest in an attempt to protect natural values from infrastructure or construction development (decision No.162/2005 of the Harghita County Council).

A chestnut grove, herbal medicine, an open-air spa, and a festival

The age of the villagers and rightsholders influences their relationships with the commons. Some areas of the territory such as the open-air baths complex are used for leisure and healing. Some members are hunters of wild boar and deer and tend to know the forests better than the others. They also declare sightings of species that have returned or are new to the area. Some commoners have an intimate knowledge of existing species of flora and engage actively in harvesting and selling traditional medicine based on herbs and plants that are picked, dried and made into teas, creams, and lotions (Papp and Dávid, 2016). One such plant is the striking blue trumpet-shaped gyertyángyökér (Gentiana asclepiadea L.), a flower that fills the pastures from late summer and into autumn. Locals organise regular meetings and workshops, open to the community and to outsiders, for transmitting traditional knowledge about plants. Edible mushrooms are also collected in the forest.

Another beloved communal territory is the sweet chestnut grove, planted by community members at the beginning of the 20th century and used by the school to teach lessons about biology and ecology. Every first Saturday of October, the community organises the Chestnut Festival using the commons’ budget and reunites members from all over, assembling for a day to celebrate their commons. This festival represents a true expression of community values.

Worries and hopes for the future

Although the Homoródkarácsonfalva Közbirtokosság has recovered well from pressures during the period of state socialism, it is not without worries. Today, the threats of invasive plants and drought are causing serious vulnerabilities. Medicinal plants are declining and others such as stag’s horn clubmoss (Lycopodium clavatum) and the blueberry bush (Afinum myrtillus L) are migrating to higher altitudes. Erosion was affecting the topsoil in small areas some years ago, but they have been planted with appropriate species and grazing was reduced to more than half of the allowed capacity.

The lack of cooperation with national authorities in managing growing interaction with potentially dangerous wildlife is also a disturbing issue for the community.

“The number of bears has increased considerably; they mostly damage the corn fields, so we had to stop cultivating some of them. We have no responsibility to manage the bears, because we have no power over them.”

The community’s vision for the future is centred around raising the quality of life for its members. They hope that their village and commons will be blessed with a favourable climate, including enough rains and water to thrive.

From a demographic point of view, children are an important part of the village’s future. For them, the community desires university education, as well as a quality of life comparable to other European countries (which can only be achieved with monetary revenue). To halt potential emigration and demographic collapse, the community feels revenue should be generated from conservation initiatives.

The community sees value in developing ecotourism services catering to a market of consumers that appreciate nature-based activities such as horse riding, walks and hiking, wildlife observation and consuming natural products. The community envisions a future of rich cultural activity around the local churches as historical heritage, the chestnut orchard as a place of celebration, and around the mineral springs of Dungo (see map Vision for the future).

References and further readings

- Garda, Dezsö. 2002. A székely közbirtokosság. Státus Könyvk., Csíkszereda.

- Hartel, T., T. Plieninger, and A. Varga. 2015. Wood-Pastures in Europe. In Europe’s Changing Woods and Forests: From Wildwood to Managed Landscapes, edited by K. J. Kirby and C. Watkins. Wallingford: CABI, pp. 61–76.

- Hartel, Tibor, Ine Dorresteijn, Catherine Klein, Orsolya Máthé, Cosmin I. Moga, Kinga Öllerer, Marlene Roellig, Henrik von Wehrden, and Joern Fischer. 2013. Wood-Pastures in a Traditional Rural Region of Eastern Europe: Characteristics, Management and Status. Biological Conservation 166 (October): 267–275.

- Imreh, Istvan. 1982. Viata Cotidiana La Secui: 1750-1850. Bucharest: Kriterion.

- Imreh, Istvan. 1973. A rendtartó székely falu. Bucharest: Kriterion.

- Iordachescu, George. 2019. Wilderness Production in the Southern Carpathians. Towards a Political Ecology of Untouched Nature. IMT School of Advanced Studies.

- Opincaru, Irina‐Sînziana. 2020. Elements of the Institutionalization Process of the Forest and Pasture Commons in Romania as Particular Forms of Social Economy. Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics, October, apce.12294.

- Papp Nóra, Horváth Dávid: „Ezt nagyon tartották Édesanyámék, Nagyanyámék” – Homoródkarácsonyfalva hagyományai és népi orvoslása / Traditions and ethnomedicinal data in Craciunel (in Hungarian) Homoródkarácsonyfalvi Füzetek III. Homoródkarácsonyfalva Közbirtokosság kiadványa, Homoródkarácsonyfalva, 2016. pp 1-150. ISBN 978-606-8599-31-1

- Varga Anna. 2006. “Kis-Homoród mente tájtörténete (Landscape history of Kis-Homoród valley).” Néprajzi Hírek 1-2: 40-41.

- Varga, Anna, Molnár, Zs. 2014. The Role of Traditional Ecological Knowledge in Managing Wood-pastures. In European Wood-pastures in Transition, Hartel, T., Plininger, T. (eds). Routledge, pp.187-202.

- Varga, Árpád. 1999. Hungarians in Transylvania between 1870 and 1995; original Title: Erdély Magyar Népessége 1870–1995 Között, Magyar Kisebbség 3–4, 1998 (New Series IV), pp. 331–407.

- Vasile, Monica. 2018. Formalizing Commons, Registering Rights: The Making of the Forest and Pasture Commons in the Romanian Carpathians from the 19th Century to Post-Socialism. International Journal of the Commons 12 (1): 170–201.

- Vasile, Monica, and Liviu Mantescu. 2009. Property Reforms in Rural Romania and Community-Based Forests. Sociologie Romaneasca 7(2): 95–113.

- Vasile, Monica. 2019a. Forest and Pasture Commons in Romania: Territories of Life, Potential ICCAs: Country Report’.

- Vasile, Monica. 2019b. The Enlivenment of Institutions: Emotional Work and the Emergence of Contemporary Land Commons in the Carpathian Mountains. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 62 (1): 124–50.

- Verdery, Katherine. 2001. Inequality as Temporal Process: Property and Time in Transylvania’s Land Restitution. Anthropological Theory 1(3): 373–92.

- Verdery, Katherine. 2003. The Vanishing Hectare: Property and Value in Postsocialist Transylvania. Culture & Society after Socialism. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Community’s own publications and other sources

- “Travelling in Székelyföld along the Rivers Homoród” by Sándor István Jánosfalvi, a manuscript from 1857 published by the Minerva Rt. in Kolozsvár in 1942 and also by the Litera Publishing House in Székelyudvarhely in 2003.

- “On the banks of the River Homoród bordered by willow meads”. Collected studies about the border area between Székelyföld and the “Saxon Land” (in Hungarian: Szászföld) of Transylvania. (the collection of studies is titled in Hungarian: A Homoród fűzes partján), published by Pro Print Publishing House, Csíkszereda, 2000.

- “Homoródkarácsonyfalva” – Information Book about the Villages of Székelyföld Series. Litera Publishing House, Székelyudvarhely, 1999.

- “Rika Region”. (The book is titled in Hungarian: Rika kistérség) published by the Association for the Rika Region in Oklánd, 2003.

- “The Garden of Sweet Chestnut Trees”. Booklets about Homoródkarácsonyfalva 1. published by the Committee Responsible for the Common Estates of Homoródkarácsonyfalva, 2005.

[1] For an extended discussion of the commons in present day Romania, see Vasile and Mantescu 2009, Vasile 2018, Vasile 2019a and Vasile 2019b.

[2] For an extended discussion of the Romanian commons, including cross-regional and historical comparisons, refer to the website of the Romanian Mountain Commons Project: https://romaniacommons.wixsite.com/project.

[3] For more details about commons as forms of social economy, refer to Opincaru, 2020.