- Home

- Executive summary

- Territories

- Kisimbosa – DR Congo

- Yogbouo – Guinea

- Fokonolona of Tsiafajavona – Madagascar

- Kawawana – Senegal

- Lake Natron – Tanzania

- Qikiqtaaluk – Canada

- Sarayaku – Ecuador

- Komon Juyub – Guatemala

- Iña Wampisti Nunke – Peru

- Hkolo Tamutaku K’rer – Burma/Myanmar

- Fengshui forests of Qunan – China

- Adawal ki Devbani – India

- Tana’ ulen – Indonesia

- Chahdegal – Iran

- Tsum Valley – Nepal

- Pangasananan – Philippines

- Homórdkarácsonyfalva Közbirtokosság – Romania

- National and regional analyses

- Global analysis

Largely occupied by the Indigenous Maasai People, this spectacular territory of life is adjacent to Oldonyo-Lengai, the Mountain of God, an active volcanic mountain in the country. Named after Lake Natron, the world’s most critical breeding site for lesser flamingos, the territory is home to diverse groups of flora and fauna and forms an important corridor, ecosystem, and landscape of two World Heritage Sites: the Serengeti National Park and Ngorongoro Conservation Area. The Maasai people depend on the Lake’s wider catchment area for their livelihoods because it is the most reliable wetland area for the large dry landscape. The territory is the source of pasture and water for both livestock and wildlife throughout the years.

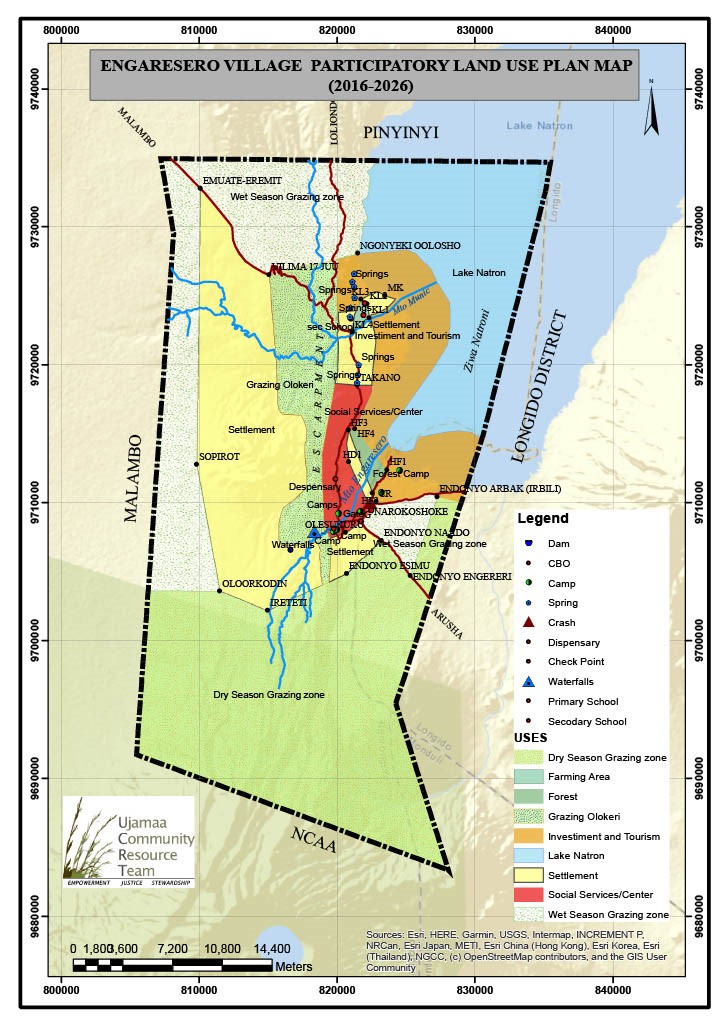

Currently, this territory is managed and governed by both customary Maasai structures and the national and international frameworks related to natural resources of national and global importance. It is administratively situated in Engaresero village, Ngorongoro District, in the northern tourism circuit of Tanzania. Engaresero Eramatare Community Development Initiative (EECDI), a community-based organization formed by the general assembly of 12,000 people from Engaresero village, manages the territory of life. EECDI’s goal is to support integrated conservation and livelihood development through tourism initiatives and cultural restoration. For years and with support from Ujamaa Community Resource Team (UCRT), EECDI has strengthened community capacity to manage, own and benefit from land and other natural resources, including wildlife. Cultural values and Indigenous knowledge are promoted to restore and create cultural heritage sites in the area. Since the territory is rich with biodiversity as well as mineral resources such as soda ash, communities have to defend their territory against both salt miners and the government’s attempts to annex this territory to establish new types of protected areas.

“We were evicted from the Serengeti area, and we moved to Ngorongoro Crater. Wild animals followed us, and we were moved again out of Ngorongoro and wild animals are still with us here in Engaresero.”

EECDI staff, group discussion, 5 November 2020

Photo: Lodrick Mika, 2020

60,000 hectares (estimated)

Custodians: 12,000 Maasai people of Engaresero village

Lake Natron’s catchment is the Maasai’s lifeline

For ages, the territory has been at the heart of the Indigenous Maasai because it has special places and trees respected for both spiritual and cultural purposes. Oldonyo Lengai remains an active volcanic mountain in the country. Maasai believe Oldonyo Lengai is the Holy Mountain of God. On the top of the mountain and waterfalls, Maasai people carry out their prayers and rituals. There are ancestors’ footprints in this protected and respected area and many archaeological places such as Pinyinyi Ward where researchers from Tanzania and abroad undertake research.

The Lake Natron territory has a unique habitat and landscape that is supported and maintained through traditional knowledge and practices such as traditional grazing calendars. The community self-identifies as Indigenous and has maintained cultural distinctiveness, traditions, and livelihoods for generations. Maa is the native language of the Maasai people; however, most Maasai speak Swahili as a national language with few educated in speaking English.

Managing the territory

Two distinct but interdependent and recognised laws – customary tenure of land rights and statutory land laws – govern the territory of life. First, under customary tenure, communities in this territory who inherited their land before independence and continued to live on it have the right to access, use, control, and to some extent own land.[1] In this customary system, institutions are made under Maasai culture and customs. The key governance structures include the Ilaigwanak (traditional male leaders) and the Morani (young men who serve as the community’s law enforcement). Outside individuals and groups of people used to enter the territory to collect soda ash. This forced the community to enact by-laws, in partnership with village authorities, to protect the lake’s salt. Also, trees used to be cut randomly in the area, provoking a response not only from elders and members of the community, but also from the village government, which assigned Morans (the male Maasai youth) to guard their territory. Morans are guided by Ilaigwanak to give warning to those who break the community’s by-laws, norms and traditions. As a result, the extraction of soda ash by residents of outside and distant villages no longer poses a major threat to this territory.

Under statutory law, community land is legally designated as ‘Village Land’, meaning the land within boundaries of a village is registered in accordance with the Local Government Act of 1982. Village land is one of three major categories of land in the country; the other categories are ‘Reserved Land’, which is held in reserve by the state for the public good, and ‘General Land’, which comprises all public land that is neither Village nor Reserved Land but includes village land that is deemed as unused. The Village Land is governed by the Village Land Act No. 5 of 1999 while General and Reserved Lands are governed by Land Act No. 4 of 1999, by the Wildlife Conservation Act (WCA) of 2009 for wildlife resources, and by the Forest Act No. 14 of 2002 for forests.[2] Although all lands are administratively overseen by the Ministry of Lands, communities have some decision-making powers and responsibilities for how land and other natural resources should be utilized and governed through their local authorities, including district councils, village councils and their assemblies.[3] A Village Council that comprises 25 members, of which one third must be women, is formed by representatives of political parties in a given village.

The statutory land laws and other resource laws allow and protect customary laws and norms that communities enact to access, use and manage natural resources in their territory. Currently, the territory has its own land use planning and zoning maps based on the two legal regimes. The whole area, apart from individual homesteads and townships, is communally owned. It supports not only environmental and conservation purposes, but also many people’s livelihoods in the territory.

However, several laws and regulatory regimes are overlapping and often contradicting one another in this territory of life. Some of the same land is governed by the Village Land Act and Game Control Areas governed by Wildlife Conservation Act of 2009, as well as being designated a global Ramsar Site. Therefore, while custodians of the territory want to protect and manage their land the way they are accustomed to, government institutions also have their own interests and visions such as establishing a game reserve on the same area.

Some tension exists between the customary and statutory governance structures, the latter of which include the village council (village government), district council and national government authorities. These are a continuation of colonial administrative structures and largely top-down authorities. Some of them were imposed by the national government during the villagisation processes of the 1970s, which affected the traditional Maasai lifestyles and systems of self-governance.

Unmatched contribution to community’s wellbeing and biodiversity conservation

The Lake Natron catchment area is the world’s most critical breeding site for the lesser flamingo, which is classified as “Near Threatened” in the IUCN’s Red List.[4] The area not only attracts flamingos and a wide variety of birds, but also hosts other charismatic species such as giraffe, zebra, antelope, warthog, buffalo, and lion, among many other mammals. This territory is the most reliable wetland area for the large dry landscape in Maasai Steppe. It forms a crucial corridor, ecosystem, and landscape of the Ngorongoro Conservation Area, including the mountains of Oldonyo-Lengai and Monduli. It is on these bases that the area is under mixed categories of conservation that include a game control area and the Ramsar Site. These are accepted by the Maasai community in the area because they are relatively compatible with the community’s livelihoods. The catchment area was declared Ramsar Site Number 1080 in 2001.[5] Nonetheless, it is largely the communities’ conservation practices that continue to sustain the area, with limited support from district and central government authorities.

To the Maasai people, this territory is a great source of livelihood as it provides settlements and grazing areas, water source, salt licks and planted and natural trees as well as key spiritual sites. There are some settled families, while others maintain a semi-mobile lifestyle as they depend on their pastoralist livelihood. Maasai communities still depend on Indigenous knowledge passed on from one generation to the other such as the use of grazing areas and pastures, medicinal plants, special trees, and soil and minerals for rituals and offerings, and handling of family matters.

The Engaresero village’s first land use planning process was completed in 2007 with the support of Ujamaa Community Resource Team. The area was mapped and specific areas of land set aside for different uses, including a settlement area where people build their houses, grazing areas used by both livestock and wildlife, and tourism sites where campsites and lodges are operating. An updated land use planning process was carried out in 2016 (see map below).

As noted above, the territory is a crucial landscape for cultural and archaeological sites and especially as the flamingo breeding site. The surrounding areas including Oldonyo-Lengai, Ngorongoro Crater and Kilimanjaro National Park are all attractive to tourists. Tented camps have been established in communal lands in the village where communities earn some income for tourists spending nights while participating in walking safaris and climbing Oldonyo-Lengai to view the active volcano crater. For example, from 2015 to 2019, Engaresero village earned an average annual income of USD 35,119 from tourism activities. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, tourism revenues declined in 2020 to around USD 8,780.[6] The revenues from tourism activities in the territory support communities in their quest to improve social services such as the construction of health facilities, teaching in schools, and provision of water to residents in the area.

Responding to internal and external threats

While this territory has faced and continues to face several threats from within and outside, the area remains in good condition because of continued efforts to keep it safe. The inhabiting community members work closely with relevant village and district authorities to enforce existing customary natural resource governance mechanisms and land use planning district and village by-laws. Key internal threats include social fragmentation fuelled by increasing tourism activities in the area as well as modern development such as roads facilitating immigration of people from other communities into the territory.

Climate breakdown is a significant external threat. Like many other dry rangelands of Tanzania, the territory is experiencing ever-increasing weather and climatic changes with long drought seasons and unpredictable rain patterns in recent years. Droughts in the area not only harm livestock keeping, which is the major livelihood activity of Maasai people, but also negatively affect health, economic and social well-being. At other times, high rainfall also causes flooding across the escapement.

Around the mid-2000s, the government, in collaboration with foreign and local investors, proposed the construction of a large-scale soda ash processing factory in Lake Natron Basin. This plan provoked a backlash from local and international communities and organisations who provided evidence that the factory could have devastating environmental impacts on the unique flamingo breeding site. Community members and their leaders strongly voiced their concerns about the dangers of this mine, including the Engaresero village chairman, who stated that “the livelihoods of the 4,000 residents of Engaresero village were in danger if the government allowed the soda ash mining.”[7] Following years of negotiations and contestations, the government moved the planned soda ash extraction project to a new site far from Engaresero village.

The governance status of the area is continuously tested. In July 2020, the Permanent Secretary of the Ministry of Natural Resources and Tourism stated that the government intends to upgrade the Lake Natron area into a Game Reserve, a type of protected area where human activities like pastoralism are legally restricted. If the proposed Game Reserve is put in place, it means the community will automatically lose access to and control over their communal land because a protected land is governed and managed by the central government through protected area legislation.

If the Game Reserve is designated, the community will also lose the revenue they generate from tourism businesses operating in their village land. Following the government announcement, villagers and their leaders wondered why there were plans to evict them again: “We were evicted from the Serengeti area, and we moved to Ngorongoro Crater. Wild animals followed us, and we were moved again out of Ngorongoro and wild animals are still with us here in Engaresero. All this is because Maasai by culture and traditions do not kill or eat wildlife, so due to our land plans in Engaresero, now the numbers of key wildlife species – giraffes, zebras and gazelles – have increased.” (EECDI staff, group discussion, 5 November 2020).

These community claims of eviction threats have existed over the past few years, but they were reported by the government owned newspaper ‘Daily News’ on 5 August 2020. The newspaper article reported the Regional Commissioner’s visit to Engaresero village to calm protesting villagers after the government’s announcement to change their village land into a game reserve area. Informing the visiting Commissioner, the Engaresero Ward Councillor Mr. Abraham Sakai reportedly said: “Our land, the only place we have called home for a long time, is about to be taken by the Tanzania Wildlife Management Authority. This is a major concern to all of us and will greatly affect our livelihood.”[8] Responding to villagers’ and leaders’ concerns, the Commissioner reportedly assured them that his office has noted their concerns and that no one will be evicted.

The Maasai community’s hope for the future

For the Maasai people, the key priority is securing tenure rights of land and other natural resources attached to it. Without these rights, their livelihoods, culture, traditions, Indigenous knowledge and history will be jeopardised. Ownership and tenure security are the developmental pillars of EECDI. Securing access to land and natural resources by formalizing collective land tenure security supports vulnerable Indigenous peoples to maintain their livelihoods and exercise their civil, social, cultural, political and economic rights that contribute to local, national, and global sustainable development.

It is on these bases that security of land and other resources are provided to the people through the Certificate of Village Land (CVL) and Customary Certificate of Rights of Occupancy (CCROs), both legal tools for protection of communal areas and wildlife habitats. The legal protection of communal rangeland and empowerment of Indigenous Maasai community in the Lake Natron territory has so far enhanced an integrated approach to both conservation and livelihoods as a lasting solution for biodiversity conservation in the Northern Tanzania rangelands.

The Maasai community in Lake Natron hopes that these legal tools and ongoing support from some government departments as well as local and international organisations will help them maintain their access to and control over their land and resources on which they depend.

[1] In the strict sense of ownership, Tanzanians do not own land. Instead, they have user rights because the radical title is held by the President of Tanzania on behalf of all the people.

[2] Sulle, E. 2017. Of Local People and Investors: The Dynamics of Land Rights Configuration in Tanzania. Danish Institute for International Studies (DIIS) Working Paper, Copenhagen: DIIS https://www.diis.dk/node/21038

[3] A village assembly comprises all the members of a village above the age of 18; it is the foundation of local government and administration as it is the institution that elects and holds village and district office bearers to account.

[4] BirdLife International. 2012. Environmental Advocacy at Work: Lessons Learnt from the Campaign to Save Lake Natron from the Plans to Build a Soda Ash Factory. Nairobi: BirdLife International, Africa Partnership Secretariat, p. 5.

[5] Ramsar Sites Information Services: https://rsis.ramsar.org/ris/1080 [accessed 13 July 2020].

[6] Statistics obtained from unpublished Engaresero village revenue and expenditure reports.

[7] BirdLife International. 2012. Environmental Advocacy at Work: Lessons Learnt from the Campaign to Save Lake Natron from the Plans to Build a Soda Ash Factory. Nairobi: BirdLife International, Africa Partnership Secretariat, p. 43.

[8] Daily News, 5 August 2020. Tanzania: Villagers Protest Eviction Plan On Lake Natron Shore. The government of Tanzania News Paper. Available at: https://allafrica.com/stories/202008031002.html [accessed 12 November 2020].