- Home

- Executive summary

- Territories

- Kisimbosa – DR Congo

- Yogbouo – Guinea

- Fokonolona of Tsiafajavona – Madagascar

- Kawawana – Senegal

- Lake Natron – Tanzania

- Qikiqtaaluk – Canada

- Sarayaku – Ecuador

- Komon Juyub – Guatemala

- Iña Wampisti Nunke – Peru

- Hkolo Tamutaku K’rer – Burma/Myanmar

- Fengshui forests of Qunan – China

- Adawal ki Devbani – India

- Tana’ ulen – Indonesia

- Chahdegal – Iran

- Tsum Valley – Nepal

- Pangasananan – Philippines

- Homórdkarácsonyfalva Közbirtokosság – Romania

- National and regional analyses

- Global analysis

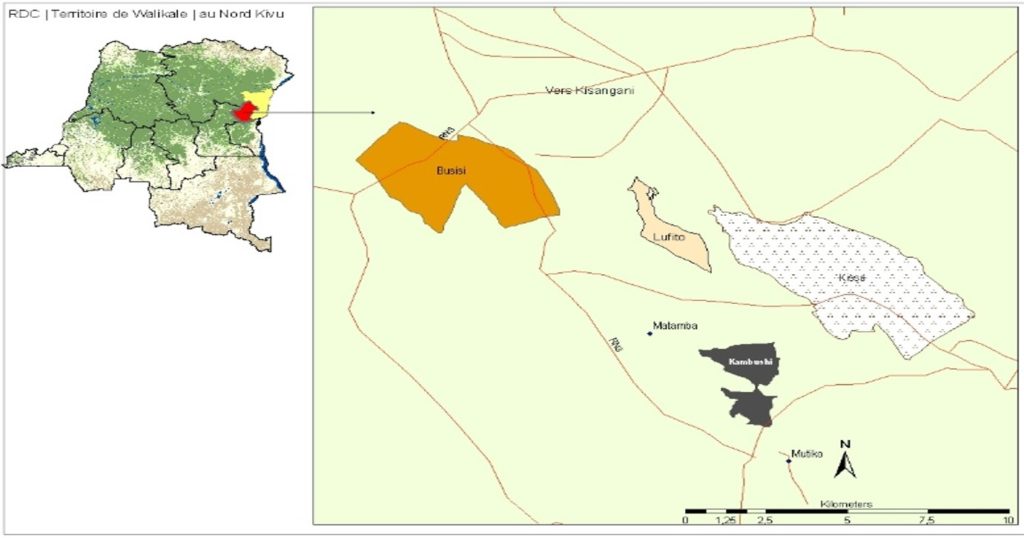

Kisimbosa, the “fertile ancestral land”, is the territory of life of the Bambuti-Babuluko Indigenous peoples of Walikale, one of the administrative units of North Kivu province, in the east of the Democratic Republic of Congo.

This “fertile ancestral land” extends over 5,572 hectares of a mountainous tropical forest ecosystem, criss-crossed by several freshwater rivers. The isolated Kisimbosa area forces them to live off local resources; their food, medicines and building materials mainly come from the forest. Their forest contains one of the last areas of primary tropical forest cover in a region that has otherwise been plagued by numerous conflicts, including armed conflict, for more than 20 years. Kisimbosa is part of the Walikale forests, still spared by the intensification of agro-pastoral activities and by the significant degradation and deforestation that the rest of North Kivu province is experiencing.

“The forest is considered by the Indigenous Bambuti-Babuluko Pygmies not as a simple geographical space covered with trees but as a living being in its own right that interacts with them.”

Joseph Itongwa Mukumo

Photo: Christian Chatelain

Armed conflict has pushed refugees (especially Rwandan Hutu populations) into the Walikale forests, thus creating new and increased pressure on natural resources. To counter this, the indigenous people of Kisimbosa have used their traditional management system to strengthen restoration of extinct species, particularly the great apes. Several groups of chimpanzees have been re-established in the Kisimbosa forest, which is habitat to other plant and animal species (including endemic species) such as Congolese peacocks, leopards, monkeys, and green pigeons.

The Bambuti-Babuluko community of Kisimbosa (made up of four sub-communities or “families”) is generally recognised as Indigenous – and thus the oldest community in the area. Their own dialect has been slowly diluted so they now speak Kirega and Swahili, the languages of local, non-indigenous groups. The Bambuti-Babuluko Peoples today lead a sedentary lifestyle on their ancestral territory, which provides them with their livelihoods, thanks to its healthy conservation status.

5,572 hectares of

tropical forest

Custodians: Indigenous Bambuti-Babuluko peoples of Kisimbosa community, 6,100 persons

Emblematic species: chimpanzees

Traditional activities of the Bambuti-Babuluko community include gathering food and medicine, hunting, fishing, and the collection of materials needed for housing. Their cultural and spiritual activities take place in specific geographical locations such as sacred sites dedicated to the memory of ancestors, leopard caves, water points for green pigeons, and areas reserved for initiation ceremonies of the eldest members of the family, traditional circumcision practices, and learning about life in the forest.

Management bodies and an institution of governance derived from original Pygmy families

Four families (the Mwarambu Mbula, Bamwisho Shemitamba, Bamwisho Mutima and Ekamenga Mbula) are descended from the first ancestors who arrived on the site: Malonga, Mukumo and Mabaka. Very proud of their territory of life, these four families have historically divided it into subsections according to the links that each family maintains with a specific part of the territory. It is the unity and formal mapping of all these lands, however, that allows for their effective management and governance. A community assembly is held annually and reviews the state of the forest, and identifies threats to the territory, possible causes of degradation and the responses to be made.

Kisimbosa has always had its own custodians or guardians of tradition. They are traditional leaders who, like Mr. Paul Aluta and Mukumbwa Nkango, maintain the customs and traditional rules involved in the governance and management of their environment. They are the bearers of their land’s history; they have an intimate knowledge of the land and can communicate its values and their understanding of how best to prevent its degradation. To this end, they lead traditional and cultural ceremonies related to the sacred sites, they lead initiations for young people, and they monitor expeditions in the forest. This traditional ancestral authority is today structured around two main bodies officially re-established in Kisimbosa: a Council of Elders, made up of elders from each of the four original families, and a committee of customary leaders, made up of the first born of each family lineage (Malonga family, Mukumo family, and Mabaka family).

The Council of Elders is the decision-making body of Kisimbosa. It is the guardian of tradition and its role is to revitalise cultural practices and traditional rules required for the sustainable use and maintenance of Kisimbosa’s ecosystems. It also deals with conflict resolution on a daily basis and, at annual community assembly meetings, discusses the various problems of the territory of life and its future.

A community monitoring and zoning system

The committee of customary leaders is the management body of Kisimbosa. It supervises the day-to-day management of the community forest, which includes the application of conservation rules, sustainable use of its resources, and surveillance. It is based on a division of the territory into three types of zones:

- Strict protection zones in which the strong values of the community are made sacred, such as the tops of the Mashugho and Chankuba mountains, where traditional ceremonies are regularly organised. These areas are prohibited from any agricultural activity.

- Areas of ongoing and permanent activities for the life of the community, where agriculture is allowed.

- Areas of temporary or seasonal activities, such as certain portions of rivers used for communal fishing (Choko), or some forest areas used periodically for hunting.

This zoning system is coupled with sustainable management customs that have been passed down from generation to generation, for example, fishing (collective and seasonal fishing practices without metal objects), agriculture (prohibited zones), and gathering or hunting (hunting of certain animal species authorised only for ceremonies and rites, hunting with nets and not with wire ropes, prohibition of hunting in the rainy season in certain places because the animals find refuge there, and so forth). A monitoring committee called “Bansoni” has also been set up to codify and enforce the regulations known as “Kanuniyapori”. Sixteen volunteers (four people per village), including three women, patrol the entire area of Kisimbosa once a month.

While the Kisimbosa territory has its own institution of governance based on this customary system, it has also obtained the status of a “Forest Concession” from the Congolese administration. This status gives the community the possibility to decide for itself how the forest is managed and, based on this status, the Kisimbosa community has chosen to make the forest a conservation area. This does not, however, give Kisimbosa the status of Congolese Protected Area (which would then be referenced in the list of official Congolese protected areas). It is nevertheless an important step towards the legal recognition of other types of conservation and governance systems for conserved areas, in addition to existing state-regulated areas.

Living forests are a highly respected source of sustenance for the communities

The Kisimbosa territory provides high-yielding agricultural production, medicinal products, sustainable hunting and fishing, timber and woods for making tools and furniture, various tree saps with elastic, sticky, flammable, and lighting properties. Other useful forest products such as lianas, bamboos, and marantaceae leaves in which cassava, a major food staple for the whole of Central Africa, is wrapped. The population also depends on the forest for cultural and spiritual reasons, including honoring ancestors, seeking leniency from the spirits, maintaining initiation rites, cultural dances, and ceremonies for conflict resolution and for coming of age. The forest is considered by the indigenous Bambuti-Babuluko Pygmies not as a simple geographical space covered with trees but as a living being in its own right that interacts with them. It is a source of pride and a vital necessity with which every indigenous Bambuti person strongly identifies.

The extreme isolation of this territory creates some particularly challenging living conditions for the community. The distance from markets makes it difficult to easily exchange harvested produce and essential manufactured products. However, this isolation also helps to maintain the area’s rich biodiversity and the high quality of its forest products. The “stability” offered by this territory has enabled the community to be protected from total economic poverty, unlike other indigenous communities in similar contexts whose land has been despoiled and can no longer practice their agricultural activities, hunting or cultural rites.

Forests threatened from outside by poaching and mining and inside by discouraged communities

Kisimbosa is threatened by several converging phenomena. The first and perhaps oldest is poaching, a clear and growing threat. Bantu hunters from other parts of the country carry out disorderly and unsustainable hunting practices. They hunt everything, at all times, with all types of weapons (firearms, weapons of war, wire ropes, etc.), mainly for commercial reasons, and sometimes benefiting from alliances with local government leaders.

The community of Kisimbosa has been aware of the need to preserve its culture and environment against this type of threat for more than 30 years. Since 2008, it has been fully committed to this goal, as illustrated its self-recognition as an ICCA in 2013 (with technical support from the ICCA Consortium). The recognition of their territory of life by the community itself, as well as its legal recognition as a Forest Concession by the State, has revitalized and strengthened its governance structure. As a result, the committee of customary leaders has been mobilized and a forest watch has been organized. In addition, members of the community, depending on their own capacity and availability, would now no longer hesitate to resort to state services in cases of poaching and other environmental abuses.

Nevertheless, while the new regulations were successful in limiting illegal hunting by “outsiders”, they have not all been universally accepted by neighboring communities. Indeed, since the recognition of the forest as an ICCA by the community of Kisimbosa, it is prohibited to everyone to access it for hunting and setting traps in quantity. Neighboring communities therefore question regulations and the forest monitors of Kisimbosa face sometimes violent threats.

A third threat to Kisimbosa is more internal to the community. Some members of the community are becoming impatient and would like to see their forests contribute more quickly to meeting their economic and social needs, such as getting children into school, improving the health system, and meeting the various needs that require household income.

Young people are at the forefront of this threat because they have high expectations about the long-awaited benefits that come with the conservation of their forest; they find that they are not reaping those benefits quickly enough. Disappointed, they may no longer be willing to commit to the cultural codes of conduct dictated to them by their elders. The abandonment of certain cultural values that are needed to maintain Kisimbosa’s ecosystems is a threat in its own right, especially if their system of transmitting intergenerational traditional knowledge is not sufficiently strengthened.

“You children have to keep your pygmy culture but also go to the white school so that you will never be neglected by anyone again.”

Another widespread threat is mining exploration and extraction. The territory of Kisimbosa is one of the regions in which some miners have bought community land in collusion with provincial and national deputies. This represents a significant threat of eviction for certain groups from the community of Kisimbosa who, without sufficiently strong recognition and security mechanisms in place, risk losing their forests.

Lastly, even though the Congolese state has granted Kisimbosa a Forest Concession, and recognizes the community rights of the Bambuti Indigenous peoples “in perpetuity”, nothing guarantees that this same state will not retake control of this title, downgrade it or reclassify it, thus endangering the relative security these communities have acquired in their territory.

In Kisimbosa, the Bambuti-Babuluko Pygmies are proud to have saved their environment and their culture

In addition to its Forest Concession status, the main source of hope for the Bambuti community is the pride they feel in successfully preserving and securing their territory, which is in turn their source of life. They are aware they have saved their territory from loggers and locally elected officials who try to buy the communities’ land as well as from the loss of certain animal species they have managed to reintroduce. Despite initial difficulties, a lack of information, latent discouragement, and a feeling of powerlessness in the face of multiple external aggressions, the community has been able to respond effectively and now realizes, especially considering the arrival of surrounding communities fleeing their own forests which are being cleared, that their efforts have paid off.

The main objectives of the Kisimbosa community include ensuring their territory is intact for future generations, preserving its cultural, ecological and socioeconomic functions that contribute to the well-being of its inhabitants, and anticipating the alterations of seasons caused by climate change. To fully achieve their ambitions for the Kisimbosa territory of life, the community have put in place: (1) a sustained and secure traditional governance structure; (2) a land use plan; (3) a monitoring plan defined and regularly re-evaluated by community assemblies; and (4) a system of intergenerational transmission of knowledge to sustain Pygmy culture. The Kisimbosa forest is the raison d’être of the Bambuti-Babuluko Pygmy Indigenous peoples and they are proud not only to have succeeded in conserving it, but also to have their accomplishments recognized on a larger scale.

Thanks to the community’s struggle for the legal recognition of their conservation efforts, they are truly preserving the Kisimbosa forest, and the plant and animal diversity that lives therein. The Kisimbosa forest is a powerful example of how communities are conserving forests and their ecosystem processes on their own terms. It also highlights the crucial role community forests can play in carbon sequestration and fighting deforestation and degradation – all part of the Congolese government’s wider strategy to combat climate change.

Following the example of Kisimbosa, many other communities have declared their ICCAs and have formed the National Alliance for Support and Promotion of Indigenous and Community Heritage Areas in DRCongo (ANAPAC).[1] Let us hope that the Congolese state and many other rural communities, in the DRC and in the sub-region, indigenous or not, learn from this experience.

[1] Alliance Nationale d’Appui et de Promotion des Aires du Patrimoine Autochtone et Communautaire en RDCongo, ANAPAC.