- Home

- Executive summary

- Territories

- Kisimbosa – DR Congo

- Yogbouo – Guinea

- Fokonolona of Tsiafajavona – Madagascar

- Kawawana – Senegal

- Lake Natron – Tanzania

- Qikiqtaaluk – Canada

- Sarayaku – Ecuador

- Komon Juyub – Guatemala

- Iña Wampisti Nunke – Peru

- Hkolo Tamutaku K’rer – Burma/Myanmar

- Fengshui forests of Qunan – China

- Adawal ki Devbani – India

- Tana’ ulen – Indonesia

- Chahdegal – Iran

- Tsum Valley – Nepal

- Pangasananan – Philippines

- Homórdkarácsonyfalva Közbirtokosság – Romania

- National and regional analyses

- Global analysis

The Philippines is the world’s second largest archipelago of 7,641 islands[1] covering 30 million hectares of land territory. On a per-hectare basis, it harbours more diversity of life than any country on Earth.[2] It ranks highest in the Southeast Asian region in terms of native tree species[3] and is the fourth in the world in terms of bird endemism, making it a top global conservation priority area. There are an estimated 14-17 million Indigenous peoples in the Philippines (between 10-20 percent of the total population), coming from 110 distinct Indigenous ethno-linguistic groups. There are approximately 175 different spoken languages in the country, some influenced by the 300-year regime of the Spaniards, some entirely distinct (especially those in the heights of the mountains) and most developed through Austronesian roots.[4] They practice diverse livelihood strategies across the country, from coastal fisheries[5] and gathering of forest products[6] to shifting cultivation and the famous rice terraces of the Cordilleras.[7] Indigenous peoples’ customary territories are known as ancestral domains and comprise the lands, inland waters, coastal areas and natural resources within their territory.[8] Ancestral domains are considered private lands but are community-owned and held under long-term possession or since time immemorial under the concept of Native Title.[9][10]

Recognition of Indigenous peoples’ rights in the Philippines

The Philippines’ cultural diversity is recognised by the 1987 Constitution with at least six provisions ensuring the rights of Indigenous peoples. Further, the declaration of the Indigenous Peoples Rights Act[11] expressly guarantees the rights of Indigenous peoples to their ancestral domains through five bundles of rights: (1) right to ancestral domains; (2) right to cultural integrity; (3) right to self-governance and empowerment; (4) right to social justice and human rights; and (5) right to enter into and execute peace agreements.

Under the Indigenous Peoples Rights Act, two titles can be issued: Certificate of Ancestral Domain Title (CADT), which typically covers the entire ancestral domain and can span across multiple communities; and Certificate of Ancestral Land Title, which usually covers lands owned by certain clans and is therefore smaller than a CADT. The process to secure a CADT by evidence of a Native Title is relatively complicated, tedious and has become ministerial to the extent that it actually counters the original intention of the law, which is to protect the rights of Indigenous peoples.

State recognition of Native Title resulting in a Certificate of Ancestral Domain Title (CADT) begins when a concerned Indigenous community solicits the same with the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples.[12] The process of formal recognition of an ancestral domain includes self-delineation, sworn statement of elders as to the scope of traditional territories, written accounts of customs and traditions, political structure and institution, pictures showing long-term occupation such as those of old improvements, burial grounds, sacred places and old villages, historical accounts, plant survey and sketch maps, anthropological data, genealogical surveys, descriptive histories of traditional communal forests and hunting grounds, landmarks such as mountains, rivers, creeks, ridges and hills, and write-ups of names and places derived from the native dialect of the applicant community.

When perimeter maps are complete with technical descriptions, these are published in a newspaper of general circulation once a week for two consecutive weeks to allow other claimants to file opposition within 15 days from date of publication. Once certified by the Chairperson of the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples, the secretaries of the Department of Agrarian Reform, Department of Environment and Natural Resources, Department of Interior and Local Government, and Department of Justice, the Commissioner of the National Development Corporation and any other agency claiming jurisdiction over the area shall be notified. This notification terminates any legal basis for the jurisdiction previously claimed. The CADT is then issued in the name of the community concerned.[13]

Biodiversity and protected areas in the Philippines

The country’s biodiversity is spread out in 15 biogeographic zones and 228 Key Biodiversity Areas (KBAs). Since 2018, 240 protected areas have been established, covering 5.45 million hectares or 14.2 per cent of the country’s territory. Of this total number, 94 have been legislated under the Expanded National Integrated Protected Areas System Act of 2018 and 13 under the previous National Integrated Protected Areas System Act of 1992 for a total of 107 legislated Protected Areas.[14] Of the total protected area coverage, 4.7 million hectares are terrestrial and 1.38 million hectares are marine areas. Protected areas form the main government strategy[15] in biodiversity conservation but have historically suffered constraints, ranging from lack of representation of communities, policy conflict, and lack of funding, which hamper decision-making.[16]

Huge gaps in protected area coverage include large tracts of high conservation value areas found outside of Protected Area boundaries, while the more disturbed and low biodiversity value areas are within Protected Areas. This points to a “lack of consideration for other effective governance system in areas of high conservation value.”[17] For instance, the country’s remaining forests coincide with ancestral domains, suggesting that traditional governance systems of Indigenous peoples are the reason for their effective conservation.

Overlaps between ancestral domains, key biodiversity areas and Protected Areas

The overlap of ancestral domains and Protected Areas is 1,440,000 hectares, while the overlap between KBAs and ancestral domains with CADTs is 1,345,198 hectares (96 CADTs out of 128 KBAs). This means 29 per cent of KBAs requiring protection fall within territories occupied by Indigenous peoples, thereby confirming the inherent inter-dependency of nature conservation with the recognition and respect for the traditional governance systems of Indigenous peoples. Furthermore, spatial analysis shows that in KBAs not covered by Protected Areas, Indigenous community conservation serves as a de facto governance regime, contributing significantly to the protection of forest cover despite absence of a declared protected area. About 75 percent of areas with forest cover are within ancestral domains, as shown in Figure 1.

Map: Philippine Association for Inter-Cultural Development

The large extent of high value conservation lands found outside Protected Areas and the stewardship stalemate between them and ancestral domains necessitates diversifying recognition of different governance systems to include Indigenous Peoples’ Community Conserved Territories and Areas (ICCAs) to ensure effective protection of these areas. ICCAs coincide with areas of greatest surviving endemism, a finding that was confirmed with evidence from sixteen sites covering a total area of 349,422 hectares. These were mapped, inventoried, documented and declared from 2011-2014 under two projects funded by the Global Environment Facility: (1) the New Conservation Areas in the Philippines Project implemented from 2011-2014, and (2) the Philippine Indigenous Peoples Community Conserved Territories and Areas Project implemented from 2016-2019. Both projects included the identification and mapping of ICCAs utilising traditional knowledge and science, documentation of Indigenous knowledge systems and practices, inventory of resources to determine the state of health of forests, and utilising the findings in the formulation of Community Conservation Plans. Besides leading the Asian region as an example of the national process required for inclusive conservation and positive outcomes, the 2016-2019 project is a recipient of the Development Aid of the Year Award 2019.[18]

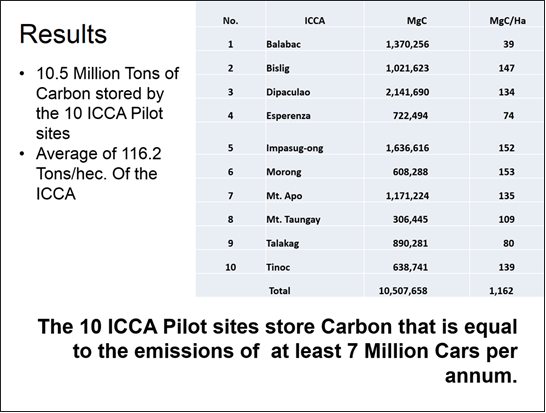

An assessment of 10 ICCAs involved in this project (Figure 2), completed by the World Resources Institute using the custom analysis tool LandMark Platform, found that they store 10.5 million tons of carbon, equivalent to gas emissions of at least 7 million cars per annum.[19] The resulting data on the carbon storage capacity of these ICCAs clearly shows the critical role they play in mitigating the impacts of climate breakdown, not only in the Philippines but also in the broader Asian region.

National and international legal context

As noted above, Indigenous peoples’ rights are recognised in the 1987 Philippines Constitution and 1997 Indigenous Peoples Rights Act. Under the latter, currently, 221 CADTs have been issued, benefitting 1,206,026 Indigenous peoples and covering a total area of 5,413,772 hectares of ancestral lands and waters, equivalent to 16 per cent of the total land area of the Philippines. This does not include areas without CADTs or areas under claims of Native Title[20] that, when combined, are estimated to be 7-8 million hectares, or a quarter of the territory of the country.

The Wildlife Resources Conservation and Protection Act of 2001 (RA 9147) provides for the conservation, preservation and protection of wildlife species and their habitats. While the Act recognises the rights of Indigenous peoples in the collection of wildlife for traditional use, it imposes control and regulation of wild animal hunting, wild foods gathering and trade.

As an amendment to the former National Integrated Protected Areas System Act of 1992, the Expanded National Integrated Protected Areas System Act of 2018 in its text secures the perpetual existence of all native plants and animals. Wildlife and KBAs are found mostly in ancestral domains. Thus, Section 13 of the 2018 Act expressly guarantees respect for Indigenous peoples’ rights to self-governance.

There is also an ICCA Bill[21] currently in legislation[22] and is moving fast in Congress.[23] The core features of the bill is the institution of a National ICCA Registry and establishing legal protections imposing sanctions for violations against ICCAs. It also aims to clarify provisions in the Indigenous Peoples Rights Act and the Expanded National Integrated Protected Areas System Act in terms of acknowledging the contribution of Indigenous peoples in biodiversity conservation. This will provide a system that would effectively support and recognise ICCAs on par with protected areas in the latter legislation, resulting in respect for and promotion of traditional governance and exercise of long-held Indigenous knowledge, systems and practices.

The Philippine ICCA Consortium or the Bukluran ng mga Katutubo Para sa Pangangalaga ng Kalikasan ng Pilipinas was formally established in 2013[24] to stand as a representation of the ICCAs in the country. It aims to promote the appropriate recognition of and support to ICCAs in the Philippines and has grown its network through the years by partnering with programmes advocating for the environment and upholding the rights of its protectors. The Consortium actively participates in calls against the Kaliwa Dam and other mega projects detrimental to the environment and Indigenous peoples’ rights, as well as against criminalisation of and attacks against Indigenous peoples and their ancestral domains.

Moreover, the Philippine government is signatory to the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (2007) and party to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (1992) and Paris Agreement (2015), the UN Convention on Biological Diversity (1992), the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (1976) and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (1976), among others.

Challenges

Policy and legal conflicts

Many of the sacred sanctuaries and forests collectively managed by Indigenous peoples overlap with “core zones” or “strict protection zones” of Protected Areas where state law declares no activities should take place. These are the same areas most important to Indigenous peoples as they sustain culture and livelihoods. It is in these areas that conflicts between nation-state and customary laws have historically emerged. These conflicts are exacerbated by implementation rules[25] where ancestral domains without CADTs that share common areas with Protected Areas will not be recognised under the Expanded National Integrated Protected Areas System Act of 2018. Challenges will persist as Indigenous peoples’ rights to exercise traditional governance over their territories will be disenfranchised. These rules could be used by the state government to displace Indigenous communities from their territories or to criminalise their traditional access to and use of resources within their territories that are overlapped by the Protected Areas. For example, the Manobos’ rescue of a Philippine Eagle was not commended but instead they were accused of illegal hunting of wildlife. The Manobos consider the Philippine Eagle as a key stakeholder and guardian,[26] hence, the need to protect and conserve its habitat in return.

Similarly, the Wildlife Act could prevent intruder migrants from wildlife collection and trading for purely profiteering purposes. However, for Indigenous peoples, the collection of herbal plants, wild honeybees and hunting wild boar is important for sustaining health and livelihood and has been a part of a culture-based resource management system that provides sanctuaries for wildlife in the first place. Policies acknowledging and respecting this relationship would help ensure protection of species and ecosystems while also upholding Indigenous peoples’ rights and dignity.

More broadly, there are also conflicts between governmental agencies responsible environmental matters and those responsible for economic growth and extractive industries such as mining,[27] with the latter generally trumping the former. Inconsistencies between agencies working on ground not only confuse key rights-holders and stakeholders but also put protection and conservation of the environment in jeopardy. The implementation of policies and legislations contrary to existing laws have highlighted the vulnerability of ICCAs in the face of such institutionalised threats and continuously threaten the Indigenous peoples whose lives are intertwined with the protection of their cradled lands and territories.

Human rights violations

The violation of human rights occurs often in the form of development aggression, including large-scale mining operations and dam projects, and encroachment of migrants who stake claims or possession over lands within traditional territories. In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and restriction rules, violations of Indigenous peoples’ right to provide or withhold free, prior, and informed consent have become rampant. Before the pandemic, 126 incidents of forcible entry into ancestral domains by businesses without free, prior and informed consent have been documented; 78 per cent of these incidents occurred in the island of Mindanao.[28] As the rush for land and natural resources scales up, asserting Indigenous peoples’ rights has led to criminalisation of these rights and the weaponisation of law itself.[29] As of August 2019, 86 Indigenous persons have fallen victim to extrajudicial killings.[30]

On 30 December 2020, nine Tumandok Indigenous leaders were killed and 16 arrested. More recently, on 7 March 2021, a day of infamy dubbed the “bloody Sunday massacre,” two Indigenous Dumagats of Rizal, Tanay, were killed together with seven activists.[31] This was immediately condemned by the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights.[32]

Recommendations and conclusions

There is a critical need for support of the Philippine ICCA Consortium’s efforts in expanding and mainstreaming community mapping, resource inventory and documentation and implementation of Indigenous knowledge, systems and practices to address tropical deforestation and impacts of climate breakdown. This can be done through expansion of and capacity to develop and implement Community Conservation Plans, priority livelihood projects and establishment of appropriate financing mechanisms (in some cases, for example, Payment for Ecosystem Services).

It is also important to establish partnerships with global conservation and environmental groups that adhere to internationally recognised Indigenous peoples’ rights, providing an additional layer of protection against the criminalisation of these rights.

The rapid decimation of Philippine forests from the 1950s to 1990s stopped at the very doorstep of Indigenous peoples’ territories. Indigenous peoples offer a counterpoint of resistance and hope so that today’s remaining forests and endemic plants and animal species can be protected within these community conserved areas. Despite passage of progressive laws and global recognition of the role of Indigenous peoples, it is still possible for the state government to exercise mandates for efforts that are already effectively being practiced by Indigenous peoples. As a result, Indigenous peoples call for respect and recognition of their rights, which in turn provides a clean and healthy environment now and for generations to come.

[1] National Mapping and Resource Information Authority, Philippines as quoted in WorldAtlas.com. 2019.

[2] Heaney, as cited in Ong. P.S., L. E. Afuang, and R.G. Rosell Ambad (eds). 2002. Philippine Biodiversity Conservation Priorities: A Second iteration of the National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan. Quezon City, Philippines: Protected Areas and Wildlife Bureau, CI-Philippines, University of the Philippines, and Foundation for the Philippines Environment.

[3] Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Center for Biodiversity. 2010. ASEAN Biodiversity Outlook.

[4] Llamazon, T. 1966. The Subgrouping of Philippine Languages. Philippine Sociological Review, 14(3): 145-150.

[5] The Molbog of Balabac Palawan lives on an island where sea crocodiles are found. Their main sources of living are fishing, swidden farming, boat making and barter trading, among others.

[6] Indigenous communities in the Philippines, having an abundant forest ecosystem, rely a lot on timber and non-timber forest resources from their forests. See, Ong, H.G., Kim, YD. 2017. The role of wild edible plants in household food security among transitioning hunter-gatherers: evidence from the Philippines. Food Sec. 9: 11–24.

[7] The Ifugao Rice Terraces has been declared as one of the UNESCO World Heritage Sites by the World Heritage Convention United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. See UNESCO WHC website.

[8] Paragraph (a), Section 3, Definition of Terms, Chapter II, Indigenous Peoples Rights Act (RA 8371).

[9] Giovanni Reyes and Joji Cariño in an exchange of comments contextualizing the term “Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities” during a consultation meeting on 10 February 2021 for the Draft Technical Report on the State of Indigenous Peoples’ and Local Communities’ Lands.

[10] Under Section 3 of Republic Act 8371 commonly known as the Indigenous Peoples Rights Act, “Native Title” refers to pre-conquest rights to lands and domains which, as far back as memory reaches, have been held under a claim of private ownership by Indigenous Cultural Communities/Indigenous peoples, have never been public lands and are thus indisputably presumed to have been held that way since before the Spanish Conquest.

[11] Republic Act 8371 enacted in 1997, House of Representatives and Senate, Republic of the Philippines.

[12] An independent body under the Office of the President mandated under the Indigenous Peoples Rights Act as primary government agency through which indigenous peoples can seek government assistance.

[13] Section 52 and Section 53 of the Indigenous Peoples Rights Act (RA 8371).

[14] Note the distinction, ‘Protected Areas’ refer to the legislated sites and ‘protected areas’ refer to those protected areas in general, areas protected by Indigenous and non-Indigenous Peoples and those legislated and non-legislated but community declared. Protected Areas are co-managed with a Protected Area Management Board. These sites receive an annual appropriation from the National budget.

[15] National Integrated Protected Areas System Act of 1992 (Republic Act 7586) amended by the Expanded National Integrated Protected Areas System Act of 2018 (RA 11038).

[16] A Protected Areas Management Board is composed of representatives from local government units from barangay, municipal and provincial levels, civil society, Indigenous communities, academe, other government agencies and private sector. The Regional Director serves as Chair of the Management Board.

[17] A USAID-funded study. “Biodiversity and Watersheds Improved for Stronger Economy and Ecosystems Resilience (B+Wiser).”

[18] Biodiversity at the Mission: PHL Envoys & Expats Recognition Awards on 4 April 2019.

[19] LandMark, the first global platform to provide maps of land held by Indigenous peoples and local communities, released new carbon storage, tree cover loss, natural resource concessions, dam locations and other data layers that shed light on the environment in which these lands exist. Computations of Carbon Storage Capacity use the following: ABOVEGROUND LIVE WOODY BIOMASS DENSITY (0.00025 degrees, Global, Zarin/Woods Hole Research Center); SOIL ORGANIC CARBON DENSITY (FAO/IIASA/ISRIC/ISSCAS/JRC, 2012. Harmonized World Soil Database version 1.2. FAO, Rome, Italy and IIASA, Laxenburg, Austria); INTACT FOREST LANDSCAPES (Potapov, P., M. C. Hansen, L. Laestadius, S. Turubanova, A. Yaroshenko, C. Thies, W. Smith, I. Zhuravleva, A. Komarova, S. Minnemeyer, and E. Esipova. 2017. “The last frontiers of wilderness: Tracking loss of intact forest landscapes from 2000 to 2016.” Science Advances 3: e1600821).

[20] Refers to areas where Indigenous communities opt not to solicit formal government recognition of ancestral domains into CADTs.

[21] The principal authors of the Bill are Senator Hontiveros, Congresswoman Legarda, and Congresswoman Acosta-Alba. The Philippine ICCA Consortium, along with other support groups, is an active member of the technical working group of both Houses of Congress. Read the proposed Bill here.

[22] The Bill has been deliberated twice in the Senate, which called for the consolidation of the two versions submitted by Senator Revilla and Senator Hontiveros. The Bill passed first reading in the House of Representatives and (at the time of publication in April 2021) is currently being reviewed by the House Committee on Appropriations.

[23] Philippine News Agency, 3 December 2020. House panel OKs bill recognizing conserved IPs’ communities.

[24] The Philippine ICCA Consortium was established in February 2013, fulfilling the express call in the Manila Declaration developed and signed by Indigenous peoples during the First National Conference on ICCAs in the Philippines held from 29 – 30 March 2012. See: The Philippines establish the first national ICCA Consortium, Quezon City, 19 – 22 February, 2013.

[25] The qualifications and language of the Expanded National Integrated Protected Areas System Act of 2018 (RA 11038) is inconsistent with the implementing rules and regulations of the Act (DENR Administrative Order 2019-05). See: Implementing Rules and Regulations.

[26] The Philippine Eagle is considered a key stakeholder among Evu Menuvos of North Cotabato due to messages it sends through sounds that community members only can interpret including impending calamities, disasters and attacks on an individual member by an outsider or attacks to the community by external forces. See also the case study of the Pangasananan of the Manobo people in this report.

[27] The Tampakan mining project has long been protested by the Bl’aan community of South Cotabato, the Local Government Unit and other support sectors, but attempts to exploit what is touted to be Southeast Asia’s largest untapped copper and gold minefield are still ongoing amidst alleged environmental and human rights violations.

[28] Salomon T., 2019. Land Conflicts and Rights Defenders in the Philippines. In In defense of land rights: A monitoring report on land conflicts in six Asian countries. Quizon, A., Marquez, D., Pagsanghan, J. (eds). Quezon City: ANGOC, pp. 106-123.

[29] The Anti-Terrorism Act of 2020 (RA 11479) is facing several petitions challenging its constitutionality before the Supreme Court. The law is believed to curtail the Greater Constitutional Freedoms, which refer to the rights of the accused, rights to privacy, freedom of expression and freedom of liberty, among others.

[30] Mamo, Dwayne. 2020. The Indigenous World 2020. Copenhagen, Denmark: International Working Group on Indigenous Affairs.

[31] IDEALS, Incorporated, 11 March 2021. “Official Statement on Bloody Sunday.” Karapatan, Timog Katagalugan.

[32] Press Briefing Notes on the Philippines. Spokesperson for the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights: Ravina Shamdasani. Available in writing at ohchr.org and video at: https://youtu.be/KRBZhjV8d18.