- Home

- Executive summary

- Territories

- Kisimbosa – DR Congo

- Yogbouo – Guinea

- Fokonolona of Tsiafajavona – Madagascar

- Kawawana – Senegal

- Lake Natron – Tanzania

- Qikiqtaaluk – Canada

- Sarayaku – Ecuador

- Komon Juyub – Guatemala

- Iña Wampisti Nunke – Peru

- Hkolo Tamutaku K’rer – Burma/Myanmar

- Fengshui forests of Qunan – China

- Adawal ki Devbani – India

- Tana’ ulen – Indonesia

- Chahdegal – Iran

- Tsum Valley – Nepal

- Pangasananan – Philippines

- Homórdkarácsonyfalva Közbirtokosság – Romania

- National and regional analyses

- Global analysis

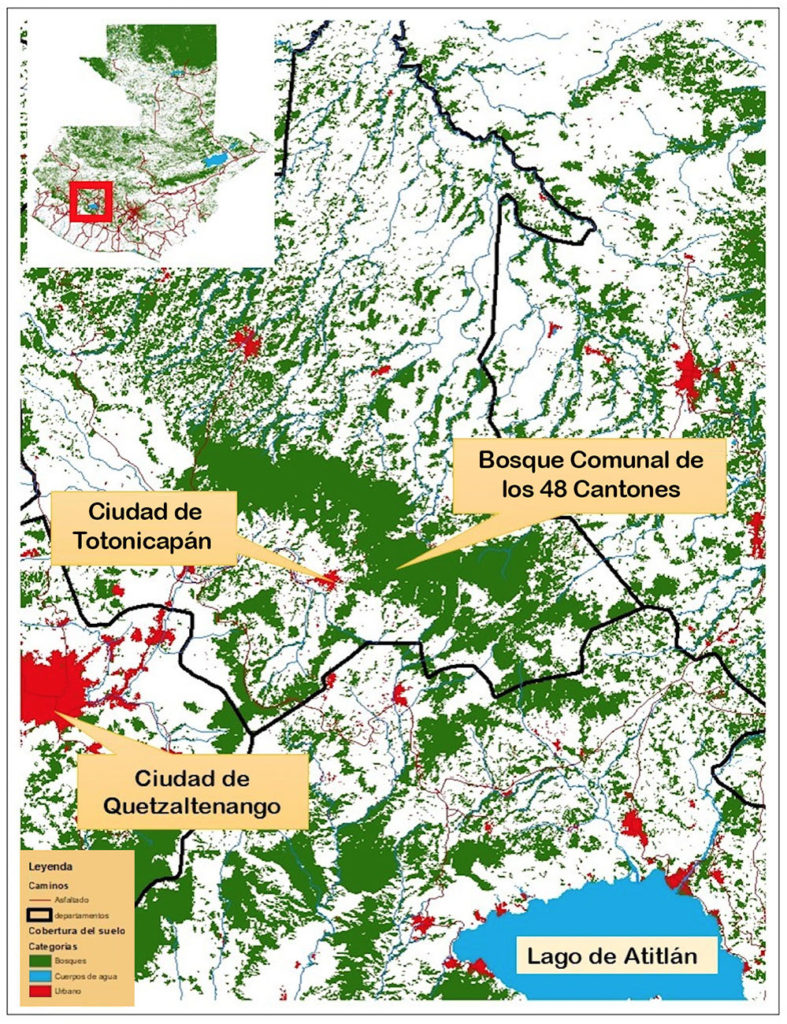

The Communal Forest of the 48 Cantons of Totonicapán is a powerful territory of life in Guatemala. Its Indigenous governance system is based on a worldview of equity, inclusion and sustainability principles, which for five centuries has supported the Maya K’iché people of Totonicapán. Thanks to this system, which prevails in a large part of the Indigenous territories in the highlands of Guatemala, the forest maintains its ecological, cultural, social and economic values such as food, medicinal plants, water sources, biological diversity and mitigation of climate breakdown.

Komon Juyub (the Communal Forest of the 48 Cantons of Chwimeq’ená[1]) is sacred to and protected by the Maya K’iché people of Totonicapán based on sociocultural values, including identity and ancestral history.[2] Numerous ceremonial sites are located in this forest, along with more than 1,500 water sources that supply the communities. It also provides food such as mushrooms, edible and medicinal plants, as well as firewood and timber for subsistence, and many families graze their sheep there as their main way of life.

“The old forest of Totonicapán is a symbol of collective unity, a sacred place.”

Photo: Grazia Borrini-Feyerabend

Komon Juyub is in the municipality of Totonicapán in the department with the same name. The municipality has around 104,000 inhabitants, 97 per cent of whom are Indigenous Maya K’iché.[3] The municipality remains covered with forests under different forms of tenure, including the Communal Forest of the 48 Cantons, the forests of the Parcialidades (community organizations based on kinship), and the forests belonging to private individuals.

The Communal Forest of the 48 Cantons of Totonicapán is 22,000 hectares, of which 11,377 were declared the protected area of Los Altos de San Miguel Totonicapán Regional Park in 1997.[4] The old communal forest under the ancestral governance of the Maya K’iché people is recognized for its long tradition in conservation, thanks to the collective tenure system, the strength of the community territorial government, and the multiple values, goods and services it provides for the population. The old forest is a symbol of collective unity and a sacred place.[5] The inclusive, equitable and sustainable ancestral governance model of community forest management is an inspiration for many people who visit it, both from within Guatemala and from abroad.

22,000 hectares

More than 1,500 water sources

Custodians: Maya K’iché Indigenous peoples of Totonicapán

K’axq’ol: a mission of sacrifice and service to care for, defend and protect life

The Maya governance of the Communal Forest is an expression of the right to self-determination of Indigenous peoples and is under the responsibility of the Board for Natural Goods and Resources of 48 Cantons of Totonicapán, an ancestral territorial government with five centuries of existence.[6] This government comprises a Communal Assembly that has representation of authorities elected in each community through the system of positions, locally called K’axq’ol (sacrifice and service). This community service, since its ancestral conception, has the mission to care for, defend and protect life.

The Assembly appoints five Boards of Directors: (1) Communal Mayors; (2) First and (3) Second Fortnight Marshals; (4) Hot Water Baths; and (5) Natural Goods and Resources. The latter, comprised of nine people supported by their assembly, leads the surveillance and control of the communal forest, the maintenance of forest nurseries, reforestation tasks, and conflict resolution. The rules within the community are transmitted through minutes, hearings, meetings and assemblies, as well as the so-called directives, a mechanism by which the outgoing community authorities transfer to the incoming ones the rules for the governance of the territory. In 2019, for example, it was agreed to celebrate the start of the 260-day cycle of the Mayan Sacred Calendar (Tzolkin), a decision that was left as a directive for the future Boards of Directors of Natural Goods and Resources to continue.

Despite its importance, Mayan governance based on ancestral spiritual, social and cultural principles is not officially recognized by the State. The Municipality of Totonicapán (an official local government structure) assumed control of the forest, without the consent of the people. In 1997, it proposed to the National Council of Protected Areas (CONAP) the creation of Los Altos de San Miguel Totonicapán Municipal Regional Park, managed by the Municipality. Although the designation of the communal forest as a state protected area does not have the consent of the people and the customary governance and management systems continue to operate regardless, a certain degree of coexistence and some coordination has been developed since then. For example, CONAP supports the 48 Cantons with a technical advisor who works exclusively with them (the only case in the country that has this support). Controlling and reporting illegal activities in the forest are supported by the National Civil Police and the Courts of Justice. The custodians have a specific office and access to computer equipment, cameras, cell phones and GPS.

Monitoring is a central element of the governance and vigilance exercised by the Board of the 48 Cantons. This is conducted through annual walking tours in the forest during the change of the Board. With participation of the incoming and outgoing authorities, accompanied by a large number of community members, the tour not only serves to identify violations and discuss actions in this regard, but also to transmit knowledge about the territory of life and its multiple values. This monitoring practice is widely used by communities with communal forests in the Western Highlands.

The governance is strengthened by alliances with various entities such as universities, ecological organizations, government entities and cooperation agencies. Recently, the Board of Natural Goods and Resources of 48 Cantons has had outreach, exchange and internal discussion with the ICCA Consortium (a non-profit global association dedicated to ICCAs—territories of life), along with the national ICCA network in Guatemala.

A territory supporting numerous lives and life forms

The Komon Juyub territory preserves and sustains important historical and socio-cultural values, including sites considered sacred such as Tzilin Chich Abaj (Stone Bell), Tum abaj (Stone Drum), Kojom Abaj (Stone Marimba), Yamanik (María Tecun), Piedra Coyote, Saq Kab’, and Chwi K’axtun. At the Caves of San Miguel, spiritual celebrations are held for family and collective well-being, such as the request for rain, the blessing of seeds, the protection of community life and the Waxakib Batz (the 260-day cycle of the Maya sacred calendar Tzolkin).

The territory has high hydrological value since this is the location of the headwaters of four hydrographic basins that mark the watershed towards the Gulf of Mexico, the Caribbean Sea, the Pacific Ocean and also the main sources that supply Lake Atitlán (one of the main tourist attractions in the country). For local residents, the water they consume is of fundamental value. Its sources are in the communal forest, so having sustainable access to water is a main motivation for efforts to conserve the territory of life. The communities are organized into Water Committees that manage the provision and maintenance of household water services includes fees. But they must also contribute their K’axq’ol when applicable and participate in forest maintenance activities such as reforestation and fire control.

The population of Totonicapán has an income below the national average and is located in the economically poorest area of the country. Until two decades ago, the forest was the main source of wood supply for producing furniture, which is one of the main economic activities in the municipality. The forest’s status as a state protected area has limited local access of wood and thus the contribution of the forest to local livelihoods. However, about a thousand families living in the 16 communities closest to the forest supplement their agricultural, artisanal and commercial production activities with the collection of non-wood forest products, constituting up to 20 per cent of their subsistence, such as honey, fruits, 30 edible species of wild mushrooms, and medicinal plants.

This territory of life is in a high mountain ecosystem, 3,000 meters above sea level, with a high degree of endemism. It is the main location of endemic tree species included in the List of Threatened Species such as Guatemalan fir or pinabete (Abies guatemalensis Rehder), six species of pine (Pinus sp.), madrone (Arbutus xalapensis), five species of birds, including the horned guan (Oreophasis derbianus), ten species of mammals, including rabbits (Sylvalagus spp) and coyotes (Canis spp), as well as other species of animals, plants, and fungi typical of this ecosystem. Its expansion and good forest cover contribute to the connectivity of landscapes between the high forests and the lower altitudinal lands. Finally, the forest helps reduce soil erosion, retain carbon, and mitigate the impacts of climate breakdown such as prolonged droughts, heavy rains, and rainstorms.

Overlapping legal and governance systems and threats to the territory of life

Because of the communal or collective land tenure, the main legal entities are the communities of the municipality of Totonicapán, grouped in the organization of the 48 Cantons, where principles of their own legal system are applied to regulate use, access, and territorial control. However, the land titles, which are held in the power and in the name of the K’iché people of Totonicapán, are disputed by the Municipality of Totonicapán. Half of the communal forest territory is registered as a state protected area, under which official norms established by CONAP prevail. There is an overlapping of rights between the legitimate tenure and ancestral governance exercised by the 48 Cantons, the Municipality’s state-recognized ownership, and the government management of the territory as a state protected area. This lack of clarity generates disputes and uncertainty in decision-making, especially regarding access, use, and administration of government resources and external cooperation for the territory. Legal insecurity and the lack of appropriate recognition and support for the 48 Cantons’ Board of Natural Goods and Resources, who are the true custodians of the territory, may be a long-term threat, but it has not been an obstacle for community governance to remain in force until now.

Given its leadership and convening capacity, the organization of the 48 Cantons also faces being co-opted by political parties, government officials and economic actors who want to take advantage of its organizational potential. Furthermore, the migration of young people to other countries is creating an intergenerational gap that affects the governance and management of the territory. Another threat is the looting of forest products for commercial purposes, especially firewood, timber and products that are used as Christmas decorations (e.g., moss, bromeliads, pinabete), a situation that requires efforts to increase control and surveillance during that season. Also, the pine beetle (Dendroctonus spp) has damaged large areas of the pine forest (Pinus oocarpa Schiede ex Schltdl); this phenomenon has been spreading around the world’s forests, fuelled by warming temperatures.

The control and surveillance system, as well as the decisions made by the 48 Cantons’ Natural Goods and Resources Board of Directors, help counter these threats and prevent and reduce the intensity of conflicts. The communities are aware of the threats to their ancestral territory and discuss in assemblies how to face them. This includes prioritizing for the three State organisations those decisions that affect them, for example, the justice system and the fight against corruption, projects of extractive and hydroelectric industries, as well as proposals for a national water law.[7] The organization of the 48 Cantons regularly takes a stand regarding issues affecting the political, social, economic and environmental situation of the country, demonstrating again their internal power and integrity as an Indigenous institution.

Self-declaring the communal forest as a territory of life

Totonicapán continues to be a bastion of resistance due to its own Indigenous organizational model.[8] Their fight for the defence of the territory has been constantly repressed by the State, from the famous uprising of the Maya K’iché people of Totonicapán, led by Atanasio Tzul and Lucas Akiral in 1820,[9] to the Alaska Massacre of 4 October 2012, where six Indigenous Maya K’iché were killed by military personnel during a peaceful demonstration.[10] However, the population remains firm in its vision of keeping extractive industries, mainly mining, monoculture and hydroelectric industries, which are considered harmful due to their environmental and social costs, far from their territory.

Faced with the interest of various sectors to have a water law, the 48 Cantons require respect for their right to give or withhold free, prior and informed consent to anything that might affect their territory of life (such as projects developed by the State), so as to not have their rights violated as true custodians of the territory and water sources. Today, the organization of the 48 Cantons aspires for the State to recognize and reward their full governance system as custodians of the ancestral territory and the communal forest.

During this 200-year commemoration of the uprising of the Maya K’iché people of Totonicapán, the community proposes to declare the Communal Forest as a territory of life. The objective is to strengthen the 48 Cantons’ Natural Goods and Resources Board and document the experience of hundreds of years of autonomous control over the forest. The Board wishes to share its governance experience with other peoples and communities, learn from other experiences and support mutual strengthening in Guatemala, Latin America and beyond.

[1] Chwimeq’ená, in Maya K’iché language, means the place above hot water. After the Spanish invasion, this place was renamed San Miguel Totonicapán. In the Nahuatl language spoken by the Indigenous people who came with the Spanish, Atotonilco has the same meaning. The local residents continue to use the native name of Chuimeq’ená to refer to their ancestral territory.

[2] Elías, Silvel, Larson, Anne y Mendoza, Juan. 2009. Tenencia de la tierra, bosques y medios de vida en el altiplano Occidental de Guatemala. Guatemala: Editorial de Ciencias Sociales.

[3] According to the 2018 National Population Census, 1.7 million inhabitants belong to the Maya K’iché people, which represent 11.5% of the total population of Guatemala.

[4] Parkswatch. Parque Regional Municipal los Altos de San Miguel Totonicapán.

[5] Ixchú, Andrea. 2012. Totonicapán. Un bosque.

[6] Stener Ekern. 2001. “Para entender Totonicapán: poder local y alcaldía indígena.” Revista Diálogo, 8.

[7] Escalón, Sebastián. 28.03.2016. La ley maldita. Plaza publica.

[8] Gamazo, Carolina. 2016. Totonicapán. El poder político de un bosque.

[9] González Alzate, Jorge. 2010. “Levantamiento K’iche’ en Totonicapán 1820: Los lugares de las políticas subalternas.” LiminaR, 8(2): 219-226.

[10] Consejo Editorial Plaza Pública. 09.10.2012. “Toto: un parteaguas para el país.” Plaza pubica.